The following material does not appear in my book Nazis in Australia. The material was edited from the chapters written by Bob Reid and me. It relates to the Special Investigations Unit’s (SIU) first investigative mission into Ukraine in December 1989 to interview witnesses regarding allegations that there were Nazi war criminals living in Australia, with a view to bringing prosecutions against those Nazi collaborators.

Not long after I arrived at the SIU in September 1988 I commenced reviewing the investigation files. It was disturbing when I realised there were very few responses to the dozens of requests the investigation teams had submitted to various governments, including the Soviet Union, as well as to international agencies and organisations, seeking their assistance in locating relevant documents and witnesses.

The majority of these requests had been submitted through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in Canberra. It was apparent to me the problem rested with the SIU and not the recipients of our requests. The cables were written in ‘police speak’, resembling a shorthand telegram, as if every word had to be paid for. To those unfamiliar with this form of writing our requests were unintelligible. Translation into another language made them even worse. It was obvious to me this was the reason most of our requests had gone unanswered. Compounding this, it became apparent that the Unit’s Russian interpreter lacked the necessary competence to provide accurate translations. After rectifying the writing defects by reissuing our requests in plain English – which could be accurately translated, and after dismissing the interpreter, we started receiving coherent replies to our requests.

Before I arrived at the SIU, Bob Greenwood the Unit’s Director, had already established contacts with the Soviet Union, specifically with the Procurator General’s Office in Moscow (in Australia the Soviet term ‘procurator’ is roughly equivalent to a ‘prosecutor’). The person in Moscow responsible for liaising with the SIU was the Soviet’s Chief War Crimes Procurator, Madam Natalia Kolesnikova, or as some larrikin Australian staff at the SIU called her, Madam Kalashnikov. I believe I met her for the first time when I was in Moscow in mid July 1989.

By then several of our Latvian, Lithuanian and Ukrainian investigation were showing promise and we were keen for our investigators to gain access to crime scenes and witnesses located in the Soviet Union. It is important to recall in 1989, the collapse of the Soviet Union during the latter part of 1991 was still a couple of years away.

Our requests to Madam Kolesnikova became persistent. When I met her in Moscow in July 1989, and pressing for our teams to gain access to the Soviet Union, I half jokingly said to her if she was going to authorise our teams to carry out investigations in her country, it might be a good idea to allow this to happen in the warmer months. It was a case of be careful what you wish for.

Whether there was anything sinister behind her decision, or whether she was also trying to be funny, approval finally came through for several SIU teams to visit the Soviet Union to undertake our investigations, with the assistance of the local Procurator General’s offices in the Regions. The not so funny part, for us, was the first missions would commence in late November that year – in the middle of the Soviet winter.

We were very pleased to receive this green light for our Soviet Union investigations to commence. We were not so keen, however, at the prospect of undertaking them in winter. It was not an option to ask for a postponement until the warmer months. So we asked our contacts in the Australian Embassy in Moscow what we could expect if we undertook our work in November/December 1989. The answer we received was, excuse the pun – chilling, we should expect to encounter temperatures of up to -40 degrees centigrade.

Planning started almost immediately for the SIU to send three teams to the Soviet Union at the end of November. One team would travel to Riga the capital of Latvia, one to Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, and one to Rovno (now Rivne) in Ukraine. All teams travelled to Moscow, via London, before heading in different directions to the three Soviet Republics.

Our team’s aim was to gather evidence in relation to several Ukrainian cases, the most prominent being Ivan Polyukhovich (in relation to crimes committed in Serniki) and Henrich Wagner (in relation to crimes committed in Ustinovka).

We knew we had to be prepared for a potentially harsh Soviet winter. The problem was there was no suitable clothing available in Australia’s warm climate, apart from ski wear. After making urgent inquiries we made arrangements to acquire some ‘down’ coats from Canada, and when we were transiting in London, we would collect pre-ordered thermal underwear from a Damart store. So when we arrived in Moscow on 1 December we were prepared for whatever the Soviet winter threw at us. In the end, the worst we encountered was -20 degrees. The thermal underwear on the other hand was hardly needed as most of our working environment was indoors in centrally heading buildings.

On 2 December 1989, Bob Reid (lead SIU Investigator) and I, together with our SIU colleagues Bruce Huggett (Chief Investigator), Anne Dowd (Criminal Analyst) and Eugene Ulman (Interpreter) travelled on an Aeroflot flight from Moscow to Rovno. We had so much luggage and technical equipment it wasn’t difficult to smuggle a carton of Fosters lager which had been gifted to us from the Australian Embassy in Moscow. We were also accompanied by Madame Kolesnikova, the Soviet War Crimes Procurator.

Moscow regional airport – on our way to Rovno (Analyst Anne Dowd far left, Bob Reid carrying the duty free bag, Bruce Huggett in front of Bob and Eugene Ulman in the light gray coat.)

Airport staff with some of our hand luggage, Eugene looking on.

Bob had always had a fear of flying and this flight did nothing to calm this fear. When we landed at Rovno, he could be heard muttering “Never again, never again.” And we never did. From that day on all of Bob’s travel from Moscow to Rovno was done by train.

Leaving to one side our rather hair raising Aeroflot (or as we called it ‘Aeroflop’) flight from Moscow, our arrival in Rovno was a relief. It was a very bleak, foggy, overcast day but we were relieved to be on the ground safe and sound. As we descended the stairs of the Aeroflot flight there was a delegation of about a dozen local Procurators from the Rovno Procurator’s Office to greet us, together with two local interpreters, Marina and Stas Kostestky.

Our welcoming party initially greeted us with some suspicion. We were amused to be told later that we were a rare group of westerners to visit Rovno. After an exchange of introductions and formalities the two groups began to warm to each other and smiles started to appear. Friendships were being formed.

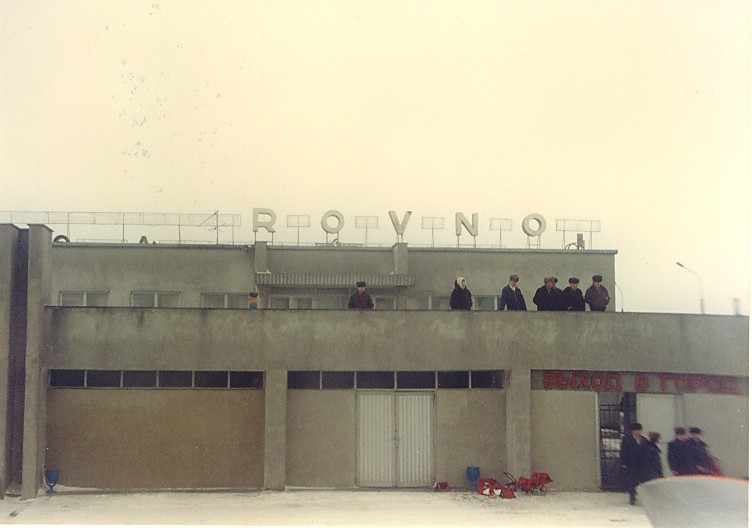

The welcoming committee at Rovno airport

The Head of the Rovno delegation was the Procurator General of the Region, Colonel Poluvoy. He proudly announced he was a very powerful person. The airport had been closed for two weeks due to heavy snow falls but he had the power to open it, which he did to allow our flight to land. It took Bob all his restraint not to hit him there and then. After the pleasantries were over we were driven to our hotel in Rovno which was going to be our home for the next month.

The ‘Mir’ hotel, Rovno.

The Hotel Mir (which means ‘Peace’ in English) was a large hotel in the centre of Rovno. We were all housed on the fourth floor and in the middle of the floor, near the elevators, were what was known as the ‘floor ladies’. These were ladies who were in charge of the floor and if you needed something you spoke to them and they tried to accommodate your request. They were very kind to us but we were sure they were KGB informants. The rooms were very basic with a single bed, a lounge, a bathroom with a shower but no shower curtain, a small hand towel, some lace window curtains and the obligatory photograph of Lenin, who Bob said good morning to every day.

Bob suspected the rooms were bugged and became convinced when he had a meeting in his room with the team. He cautioned me, Bruce and Anne not to sit on the lounge as the springs were poking up through the fabric. Before he could report the lounge to the floor ladies and ask for a replacement, two men came to the room with a new lounge saying that the other lounge was damaged and it needed to be replaced.

After unpacking and getting settled we went down to the restaurant with our interpreters and had our first meal.

The SIU team with local interpreter Stas Kostetsky, crouching next to Bob Reid.

The chap on the far right was one of the local Procurators.

On the Monday after our arrival we were escorted to the local Procurator’s office where we would be spending the next several weeks undertaking many witness interviews. The main local interpreter, Stas Kostetsky, was showing us the way to the office. We noticed, as we were trudging through the snow, there was a rather large illuminated sign on the top of a building in the main town square displaying a series of red digital numbers. I checked my watch and it was not displaying the time. We asked Stas what it was. He replied, casually, ‘oh, it shows the day’s radiation readout. It was installed following the Chernobyl disaster’. A few days later, noticing the sign had been turned off, we asked Stas why. He replied, casually, ‘oh, they turn if off when the radiation reading is too high’. To this day I’m not sure if he was having a joke at our expense.

Stas turned out to be a loyal friend. He was somewhat eccentric. He would place a magnet on his head on occasions to help with headaches he occasionally suffered. This was until Bob gave him some ‘tic tac’ peppermint candies to munch on – Stas said they cured him of his headaches. There was an occasion towards the end of our mission when Stas invited the SIU team to his apartment for lunch. He lived there with his parents, Mike and Mary he called them. At the time the Soviet Union was in the process of its inevitable collapse and the locals did it tough. Food was hard to come by. Stas emptied his pantry and commenced to open the packets and cans. We realised he was going to serve us all the food he had in his home. We stopped him. He would not listen to our protests, insisting on sharing all his remaining food with us. Such was his generosity. In later years he travelled to Australia with the witnesses who were testifying in Adelaide. He fell in love with our country. To this day I remain in touch with Stas in Rivne (even through Putin’s illegal and aggressive war). Each year we exchange Christmas cards and his are full of warm, gushing sentiments, recalling his days with the SIU staff which he says were the most memorable in his entire life. He also gives us updates about the staff from the Procurator’s office who worked closely with us. Sadly they are dying off and there are not many left alive.

Bob recalls that our interpreters became very important to us and also became good friends. As anyone who has worked with interpreters knows, it is not only important to get the exact interpretation of a conversation but also its context. It’s equally important to realise when a witness has no idea what you are talking about. Bob worked with Stas closely over his visits to Ukraine. Importantly he got to know the witnesses and was able to put them at ease. Stas told us he learnt English from listening to the BBC World Service and then attending University in Kiev. He was always telling Bob that he did not speak correct English. Stas said Bob kept cutting off the endings of his words. He claimed Bob needed to be able to say ‘baked beans’ without cutting off the end of the word. He maintained Bob would only say ‘bake bean’. Bob reckons Stas was probably right and sometimes when Bob would ask a witness a question, Stas would simply look at him with a confused frown, and Bob would have to rephrase the question. After working together for a little while Stas became accustomed to what he referred to as Bob’s ‘uneducated’ English.

SIU team with local interpreters Stas (far left) and Marina (second from right)

On our way to the Procurator’s Office – Eugene and Anne wearing the down coats we had acquired from Canada.

On our first working day, Madame Kolesnikova was already waiting for us at the Procurator’s office, and she was creating havoc. She was a thin, wiry lady who was obviously used to getting her own way. We were taken upstairs to a conference room on the top floor which would be where we did all the witness interviews. Kolesnikova asked us how we would like the room set up and after explaining how we would like it, she issued the appropriate instructions to the local staff.

Although it was freezing outside, inside it was stiflingly hot because of the central heating, and we were wearing our thermal underwear we had purchased in London. Anne Dowd moved over to the windows and opened two or three to allow a breeze through. We thought Kolesnikova was going to have kittens. She directed the windows to be closed as we would all die of pneumonia. The windows remained open but we could tell she was going to fight us on everything.

Rovno Procurators Office – we were based on the top floor during our time in the city.

Note the open windows which made Madam Kolesnikova angry.

We then began to have a conversation with our liaison Procurator, Vasily Melnishin. To us he became known affectionately as ‘Mel’. He was one of the most disorganised people we have ever met, with a face a contortionist would have been proud of. Having said that though, he always delivered the goods but not in a way Bob was ever used to. For example, when we were walking to the office Bob would often ask him how many witnesses we had for the day and Mel would answer two. When we got to the office there would often be 20 witnesses. On occasions he would say there would be 20 and there would only be two. Although it was very exasperating, we eventually got to interview everyone we needed to and on occasions some we did not want to interview.

Vasily Melnishin (far right) and the forensic Procurator we affectionately called ‘Inspector Gadget’ to my right (this photo was taken in May 1990)

On our first day, after everything had been put in place and agreed upon, we were able to start interviewing the witnesses. As agreed with the Commonwealth DPP in Australia, every interview was audio and video recorded. Each interview commenced by Mel outlining to the witness who we were and why we were in Ukraine. He then handed over the interview to us. Bruce Huggett would explain who we were and the allegations we were investigating. Bob was responsible for interviewing all the witnesses and I operated the video camera, recording each witness’s testimony.

Bob recalls the witnesses, in the nicest possible way, were very basic people who came from a rural environment and in many instances had never left it. Only a few had left their community of Serniki and only then to fight in the Great Patriotic War, the term used by the Soviets for World War II. When they presented for their interview, all wore their best clothes/suits and those who had them, the medals they had won in the Great Patriotic War. The women who were interviewed came in their best clothes.

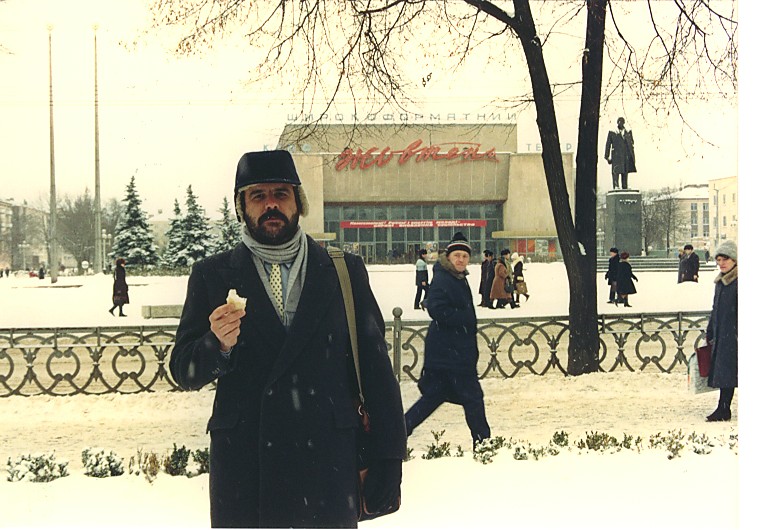

Bob enjoying an ice cream on our walk home from the Procurator’s Office

From left to right:

Eugene, ‘Mel’, me, Poluvoy, Kolesnikova, Bruce, Anne, Bob, Stas and the local Mayor of Rovno.

Our interviews continued in Rovno but we also travelled to Serniki and conducted many interviews in Zarechnye which was the administrative district in which Serniki fell. We also took the time to video record the village and, as best we could, the scenes of crime described by the witnesses. We were not sure what we were expecting when we arrived in Serniki but what we found was a village that appeared to be untouched for decades.

SIU team speaking to a witness near the Serniki mass grave

The Serniki mass grave was located in pine forest depicted at the end of the road.

The inhabitants were either quite old or very young and it appeared as though the youth had moved away. It was very picturesque looking around the snow laden fields and the frozen Stublo River. We were made to feel very welcome at the local hotel in Zarechnye which we affectionately called the ‘Zarechnye Hilton’. The hotel was run by the wife of the Zarechnye Procurator and she had the hotel repainted for our arrival. It stank of fresh paint the entire time we were there but we appreciated the effort she had gone to.

The “Zarechnye Hilton”

The rooms were even more spartan than our hotel in Rovno with no heating or hot water, only one functioning toilet and no curtains in the rooms. We went to the local shops and there was very little on the shelves except pictures of what should be there. The one overwhelming feeling of visiting Serniki and its environs was extreme poverty but what little the people had they were willing to share everything with us. It was extremely cold and we all considered it a luxury to return to Rovno and a hot shower.

As Friday afternoon approached and we had almost finished interviewing the available witnesses, we bizarrely got excited to think we were going back to Rovno and would be able to have a hot shower and a fairly decent meal.

It came to pass our protracted investigations meant we would be spending Christmas in Rovno. Our Ukrainian colleagues gave us a Christmas we have never forgotten. A third local interpreter had joined us and out of courtesy we gave her our last can of Fosters beer. We all recoiled in horror as she poured the beer into her glass and then proceeded to scoop a large amount of sour cream into the glass.

Christmas Day in Rovno – Bruce Huggett and Anne Dowd (seated)

Local interpreters Stas and Marina (standing on the left at back) next to Eugene and Bob

(Bruce and I had shaved off our beards by then.)

Bob was able to get a telephone call home to Sydney on Christmas Day and was able to speak to his family which he really appreciated.

Eventually the time came for our team to depart Rovno.

Farewell speeches

Procurator Colonel Poluvoy’s closing farewell speech

Time to say goodbye

Having already decided not to risk our lives by taking another Aeroflot flight to Moscow, on 28 December 1989 at the Rovno Railway Station, we said our final goodbyes to our Ukraine colleagues, which included most of the local Procurators, interpreters and drivers. Waving good bye at our tearful farewell, we headed back to Moscow by train. It was an overnight trip but it was much better than flying. Bob remembers waking up in the middle of the night and looking out the train window to witness a view resembling a scene from Doctor Zhivago, with snow as far as could be seen.

The team in Moscow

We flew out of Moscow on 30 December. The next day I flew back to Sydney from London, celebrating New Year’s Eve with the Qantas flight attendants. After spending New Years Eve in London, the rest of the team flew home to Sydney on 1 January 1990. During the Qantas flight Bob relived the last four weeks in Ukraine. He (and I) was satisfied there was now sufficient evidence to charge Ivan Timofeyevich Polyukhovich with war crimes.

New Year’s Eve on flight QF 2

Our flights back to Sydney signalled a close to an arduous but very successful SIU mission to the Soviet Union which saw charges being laid less than a month later against Ivan Polyukhovich, on 25 January 1990.