Apart from this opening paragraph, the material contained in this blog does not appear in my newly published book – Nazis in Australia – The Special Investigations Unit. 1987-1994. Bill has contributed a chapter for the book in which he states:

“Before joining the SIU, I worked predominantly in the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) of the Australian Capital Territory Police, and then the Australian Federal Police (AFP). I left the AFP after twenty-one years’ service and found engaging work setting up security procedures for the new Parliament House in Canberra. When that project was completed, I was ready for a change. The opportunity arose in mid-1988 during a chance meeting I had with Bob Gray, a former colleague in the Canberra CID. We had a brief chat and he explained that he was working at the SIU. Half-joking, I said to him, ‘If you get any vacancies, give me a call.’ I ended up joining the unit a few months later. By coincidence, I teamed up with Gray, who had responsibility for the seventy-five Lithuanian cases.”

Bill recalls the SIU was a unique organisation staffed by some exceptional and specialised people. He says it was a privilege to have worked alongside them. With rare exceptions, the Balkans being one, the various overseas archivists, prosecutors, lawyers, police officers, interpreters, historians, and investigators he encountered were unfailing in their help, and he often ended up forging lasting friendships.

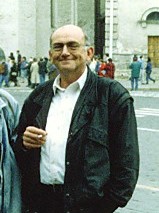

A career highlight for Bill was working for the Director, Robert (Bob) Greenwood QC. Bill reflects “He was sagacious with a positive approach. As a lawyer, he was inclined to look at ways an objective could be achieved rather than looking for difficulties. He was down to earth and he would regularly walk up and say, ‘Come on, let’s do lunch’ “.

Bob Greenwood – Moscow, April 1990

Over lunch, they would discuss the various inquiries and the prospects of appropriate outcomes. Bill liked that – “great to share a meal with such a man”. Moreover, Bill’s football coach said, “Winners have parties. Losers have meetings”. While this quote illustrated Bill’s level of thinking compared to his coach, such “lunches weren’t exactly parties, but they certainly trumped meetings”.

Approval for the SIU’s first visit to Lithuania was slow in coming and, in the intervening period, Bill had his first interview with a Holocaust survivor.

“He was an elderly and frail gentleman, with a number tattooed on his forearm. He called into the SIU office to see if we were conducting inquiries regarding Auschwitz. We were not, but I felt obliged to record his story. I thought it would have been contemptuous not to do so and one never knows, his account could have proved relevant in the future if a suspect was later identified. His account may have also proved useful to one of our internationals war crimes unit colleagues”.

“The Holocaust survivor told how he and his wife had been interned in Auschwitz and, after a period, his wife was taken to the gas chamber. He sat in the yard, devastated. Once victims were gassed, their bodies were burnt in a furnace. He watched the smoke billow from the chimney. A large flake of soot settled on his arm. He sat and stared at it before making it a keepsake”.

He would call by the office every now and then, and Bill or others would wander down to a café below and share a coffee. “Quality time”, Bill reflects. The Holocaust survivor displayed no malice. He was a true gentleman. Bill felt privileged to be in his company but, at the same time, disappointed we could not assist him. That said, Bill is sure he got some comfort in talking about his ordeal.

Bill says “as a police officer, one learns to inure oneself from emotional involvement in matters being dealt with. In an account such as the one given by this gentleman, it was hard not to feel his anguish or to imagine yourself in his situation and wonder how you would cope”. Bill recalls it was a warning to step back in future interviews and avoid emotional involvement – if that was possible. His would not be the last interview that tugged on one’s emotions. Bill’s team was about to conduct survivor interviews in Israel.

When the SIU’s first investigator, Bob Gray, left the Unit, Bill teamed up with Dick Letchford, a seconded New South Wales police detective and an original member of the SIU. Dick was a highly regarded officer who, in 1968, as a probationary constable, but with the aplomb of a seasoned officer, apprehended two armed men who had shot and murdered his sergeant and a caretaker during a break and enter in progress at Halvorsen’s boat-shed at Sydney’s Bobbin Head.

Dick Letchford

While waiting for access to Lithuania, Bill’s team compiled a list of around 30 potential witnesses from Holocaust survivors living in Israel. Bill arranged with the Israeli police to interview them. Many witnesses related to pogroms in the smaller towns of Lithuania and others to the Vilnius and Kaunas ghettos. All those nominated agreed to talk to the SIU team.

On arrival in Israel, Bill’s team first sought advice from local police officers Menachem Russak and Gadi Waterman, who were responsible for war crime investigations. Menachem was a survivor from Auschwitz and was about to retire. He was enlightening to talk to, not only about his experiences in Auschwitz, but his efforts thereafter tracking down Nazis.

Waterman arranged for one of two Israeli policewomen, Miri Drucker (now Hoffman) or Zlila Ebner-Helman, to accompany the team during their witness interviews and act as interpreter. Both could speak multiple languages, including Hebrew, Yiddish, and English. Both were experienced in war crimes inquiries. They scheduled two interviews a day, all to take place in the subjects’ homes.

One man decided against talking to the SIU, although he previously agreed to be interviewed. He found recounting his ordeals all too difficult. He was inconsolable. Bill and Dick thought it best to leave his apartment as gracefully as they could and leave him in the immediate care of his wife and Miri. Bill was grateful Miri kindly checked on him in the following days.

Bill had chosen many of these survivors because they nominated the names of men who were suspects on the SIU list of persons involved in village pogroms. Regrettably, while the team gathered some circumstantial evidence and a lot of useful information, invariably, the witnesses’ knowledge of perpetrator’s names proved to be ‘hearsay’. That was understandable. If the incident had been a village pogrom, to have survived, the person was usually elsewhere but would later learn from others what had transpired.

In these accounts, there were also instances where survivors fainted or fallen into the pit on the execution salvo of bullets and, after dark, escaped into the forests. But none were able to identify the executioners.

From Israel, Bill and Dick Letchford went to the UK to interview more Jewish survivors.

Dick Letchford’s secondment from the NSW Police finished shortly after their return from the first visit to Israel. Bill was joined in May 1989 by John Ralston, a former experienced homicide detective from the NSW Police, and Keith Innes, a former military and AFP intelligence officer.

Bill recalls Keith’s sense of humour and his “murdering of the English language” with military terminology, was a blessing to the team, especially on arduous overseas missions.

Bill has noted “to Keith, our luggage was beans, bullets, and band-aids. A Bait-layer was the name he gave the cook in our Vilnius hotel. A Tubbin was an acronym for someone who had their thumb up their bum and their brain in neutral. A battlefield was a two-way rifle range. If something went unexpectedly wrong, it was a Bang F**k which, he explained, were the two noises made when there was an unintentional weapons discharge. Heike Roberts, our German interpreter, was quite bemused by Keith calling a pen a writing utensil. While we didn’t encounter many Tubbins, we had a few Bang F**k moments when things went wrong.”

Sadly, Keith has since passed away. He was one of the most endearing persons we ever met. Bill fondly reflects on his contribution to his team’s morale and his sense of humour.

Eventually the SIU gained approval to conduct inquiries in Lithuania, commencing in November 1989.

Prior to Bill’s first mission to the Soviet Union he added an interpreter to his team, Victor Sliterus. Victor owned a successful sheet-metal fabricating plant in an inner-Sydney suburb. He migrated as a teenager with his family after the second world war. He was not a trained or professional interpreter, and Bill explained what was expected. Victor had a lot of friends and relations in Lithuania, whom Bill gathered Victor helped financially over the preceding years. It is fair to say, back then Bill and other SIU investigators viewed anybody who spoke two languages as being someone who could both interpret and translate. Generally this may be the case but it was not so straight forward. It is clear now professional interpreters are crucial to effective communication when working in multiple languages. It took Bill and other members of the team some time to build up a positive and effective working relationship with Victor, but in the end they did, and it worked well. As things panned out, he was invaluable to the team, effectively adopting the added role of tour guide. More than that, he helped the team through some cultural shocks. Victor became an important member of the team.

John Ralston and Victor preceded Bill on the SIU’s first mission to Lithuania. Bill’s first insight into the Soviet culture, when he arrived in Moscow a few days later, was Aeroflot. After a brief stopover in Moscow, he flew to Vilnius on an Aeroflot flight. For family reasons Bill was travelling by himself, having left two days after John and Victor’s departure. Bill checked in for the Vilnius flight at the Moscow desk and was taken to the head of the boarding queue. He asked the attendant, ‘What’s going on?’ She said, ‘You’ve paid in hard currency. You go to the front.’ Embarrassed, Bill declined and went to the back of the queue.

Bill recalls “The weather and the flight were rough. The flight seemed to be low, under instead of above the weather. The pilot continually swerved and banked, as if enjoying himself back in the halcyon air force days of flying around with $8 million worth of MIG strapped to his backside, rather than the more mundane task of humping around 40 tons of a cumbersome commercial aircraft with its 150 passengers”.

Bill calls to mind “two hostesses struggled down the aisle with a food trolley, fighting the turbulence and the antics of ‘Pontius Pilot’. I pointed to a large 10 litre aluminium teapot that could have doubled as a watering can on its days off and said ‘Tea, pojalusta’. Would you like something to eat with your tea?’ came the flight attendant’s reply. Great, one could speak English. ‘Yes, please. What are the choices?’ ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ was her reply. ‘Yes’ was a plyushka roll in a brown paper bag – a traditional Russian soft, fluffy, and slightly sweet pastry.”

Eventually, the plane circled over a rash of red roofs and landed with a thump. Everyone stayed seated until the flight crew paraded down the aisle on their way to the rear stairs exit, receiving a round of enthusiastic applause from the passengers on their way through. A few troubling Aeroflot incidents persuaded Bill to opt in the future for train travel where possible.

The results of Bill mission to Lithuania and the outcome of his investigations relating to the SIU’s Lithuanian suspects are fully detailed in Nazis in Australia – The Special Investigations Unit. 1987-1994.

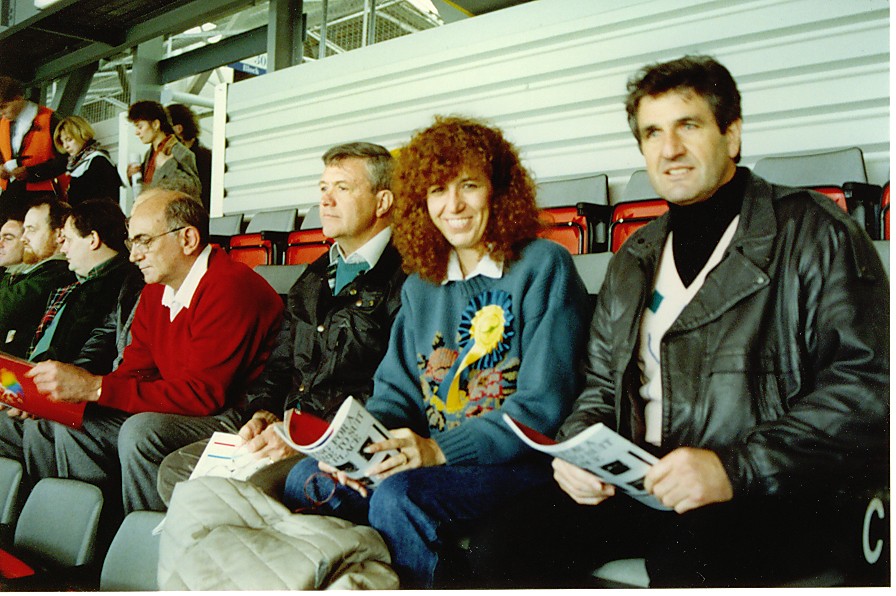

Bill Beale (far right in the black leather jacket) seated next to SIU investigators Michelle Kilburn and Keith Conwell, and Bob Greenwood the SIU Director in the red jumper. In London, October 1990

Bill made an important and professional contribution to the work of the SIU. I regard Bill as a good friend.