During my work with the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) – NAZI war Crimes Investigations – I assisted in the search for relevant World War II documents in various archives throughout the world.

One very memorable episode involved gaining access to the Secret Military Archives in Prague in March 1990. The SIU was the first war crimes unit in the world to do so. This important achievement was the result of the tireless efforts of the SIU Director, Bob Greenwood who, having gained intelligence of the archives’ existence, didn’t abandon his search for it, despite constant statements and assurances that it didn’t exist.

I recall Greenwood’s unrelenting determination to locate the ‘secret or forgotten’ archive said to hold important Nazi documents, which were said to have disappeared when a truck carrying them from Germany, crashed into a lake. It was believed the documents were retrieved and hidden away.

Greenwood commenced this quest before I arrived at the SIU in September 1988. It was rumoured the truck had been pulled out of the lake and the contents taken to Czechoslovakia where they disappeared. The rumours were the documents from the truck were being held in a place called ‘Zasmuky’ castle. Greenwood was determined to locate these documents.

There was a photograph amusingly shown around the SIU, of Greenwood and an SIU interpreter, knocking on some huge closed wooden doors at a castle in Czechoslovakia. All that was missing was the draw bridge and the moat. Needless to say no one answered the door.

His relentless searches eventually paid off, when the documents were located in Prague, in an archive located in the old Military hospital (in one of the buildings used in the filming of the 1984 movie ‘Amadeus’).

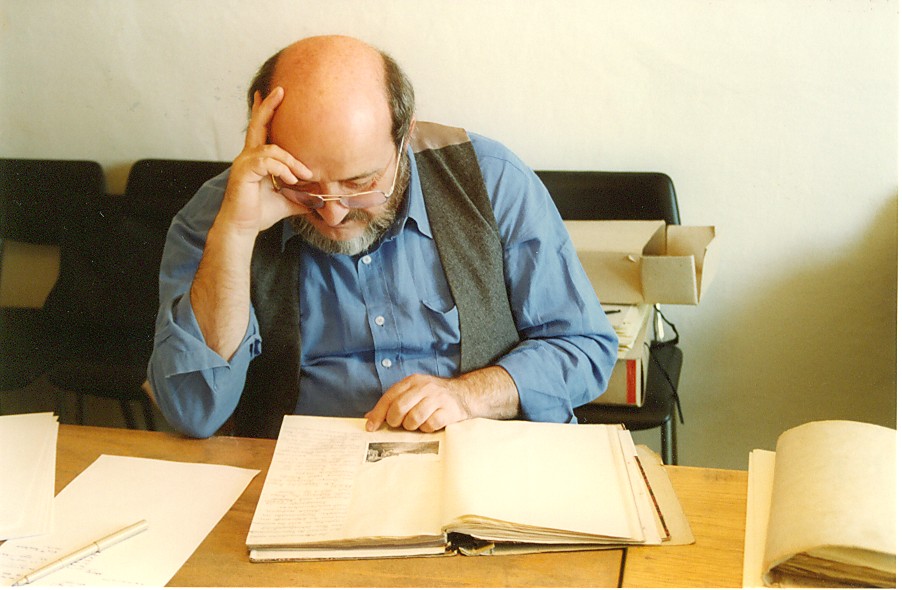

As it turned out, Professor Konrad Kwiet, the SIU’s chief historian, and I were the first Westerners to examine these documents when we were granted access in March 1990. The documents had been untouched for decades. After we had finished our examination of the documents, as a goodwill gesture, Greenwood subsequently engaged the services of a Czech research analyst to catalogue the entire document collection (at SIU expense) for the benefit of other historians and researchers.

Main entrance to the ‘Secret’ Prague Archive

While working in the archive over a number of days, we found the unheated building to be very cold and at times we were chilled to the bone. Our working conditions were less than ideal – not an uncommon occurrence when undertaking the SIU’s investigations. I had carried a portable photocopier from Sydney to make copies of any important documents we discovered.

Finishing work for the day. The tall chap, between Prof Kwiet and I, was a local historian who was assisting us in the archive. Note the photocopier and its case on the desk.

A coal heater that did very little to warm our cold and damp working area.

Professor Kwiet vividly recalls our visit to Prague on that occasion. He has stated “The work I did (at the SIU) was exciting and rewarding. I was one of the first Westerners to gain access to secret archives located in the Soviet Block, by this time already on the brink of collapse.

“The trips to Prague were particularly important. Turning up for the first time, Bob Greenwood and I were assured there were no secret archives in Czechoslovakia. We drove to Kolin, a historic town close to Prague, in an attempt to find the legendary castle of Zasmuky, the place where the SS deposited a large part of its wartime records. What we found was a rundown farming estate. Greenwood hammered on the door. After a while, a farmer opened the door and then disappeared with a shrug of his shoulder.

“On our second visit to Prague, we were told there might be some Nazi records of interest to us. When we returned, a few weeks later, Graham Blewitt and I entered the Secret Military Archives. The opening of dusty, sealed record boxes and discovering a plethora of SS records, which had until then been regarded as lost, was one of the most memorable moments of my professional career. Graham found my excitement contagious.

Prof Konrad Kwiet showing his excitement on finding the documentary treasure trove.

“Among the records were German police reports, telegraphic messages sent from the summer of 1941 onwards, to Berlin Headquarters. The messages transmitted dates, places, units and personnel relating to the first killing operations in the (Nazis) newly conquered territories of the Soviet Union.

“We established these documents had been intercepted and deciphered by skilful code breakers in (the famous) Bletchley Park (in England), the wartime headquarters of British Signals Intelligence. Copies were sent to the Americans, stamped ‘Most Secret’’ and specially marked: ‘To be kept under lock and key: never to be removed from office.’

“In 1996 (long after the SIU had closed its doors for the last time) Richard Breitman, the longest serving historical consultant of the SIU, discovered the transcripts at the National Archives in Washington DC. Another highlight of my career was when Breitman and I compared the German originals I discovered in Prague with the Allied decoded documents, which clearly confirmed a disturbing insight. Even after the war, the British and American governments had shown no interest in handing over this material to any of the war crimes commissions and trials.

“The so called ‘Ultra System’ or ‘Ultra Success,’ deciphering with the help of the Enigma machine, had been vital to the Allied WWII victory. National and political interests dictated keeping the code breaking success secret. The West maintained its deciphering superiority over the East, this time as a weapon in the emerging Cold War. Put another way: keeping official secrets from the Soviets and others was considered more important than bringing Nazi killers to justice. As Richard Breitman put it: ‘There always seem to be higher priorities for governments and their defenders, than swift action against genocide and its perpetrators. That may be one reason why some people continue to believe they can get away with mass murder in the pursuit of political goals.’

“At any rate, the opening of the Secret Archives in Prague provided a fresh and decisive impetus for research on the Nazi Regime and its genocidal policies. I would also argue both the old Nazi war crimes debate and the new modern war crimes debate had a great impact on jurisprudence, especially on international criminal law. At many universities, teaching and research programs have been introduced which are centered on the study of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide where earlier such programs hardly existed.”

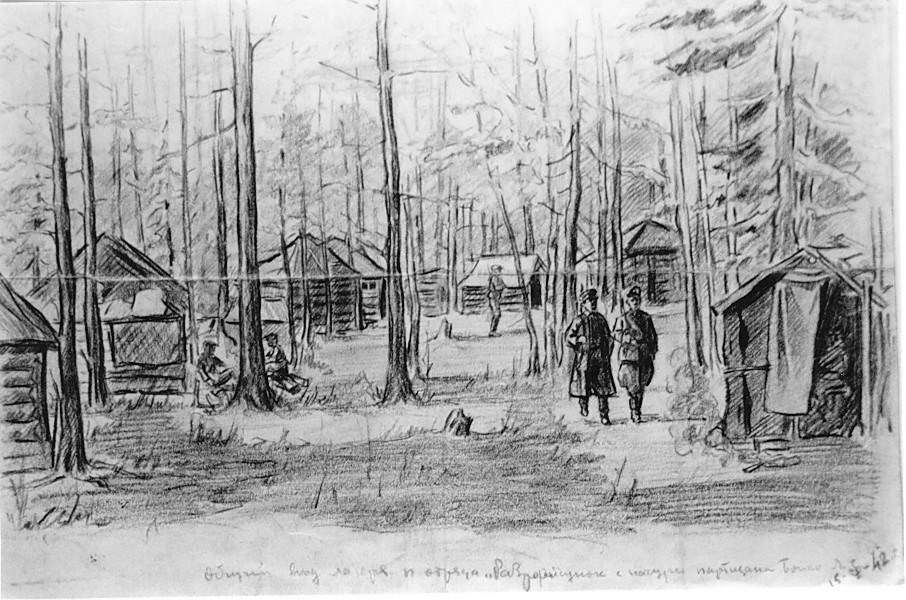

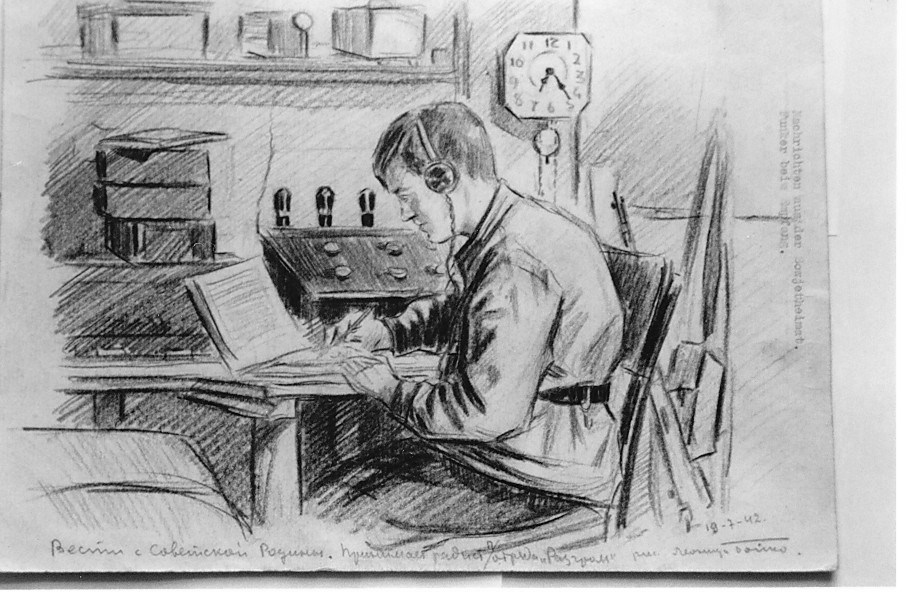

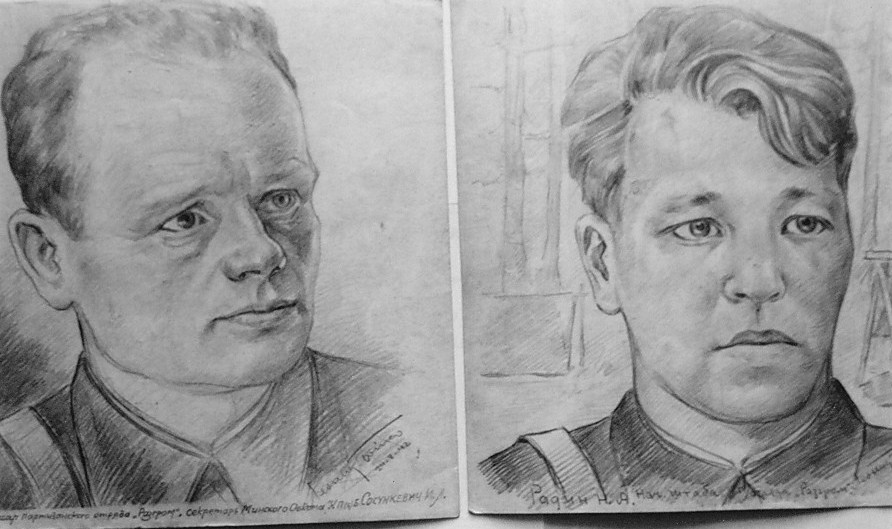

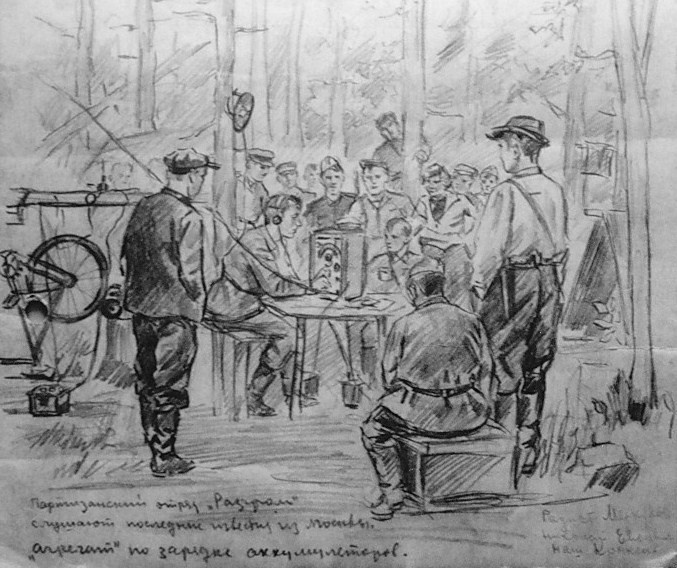

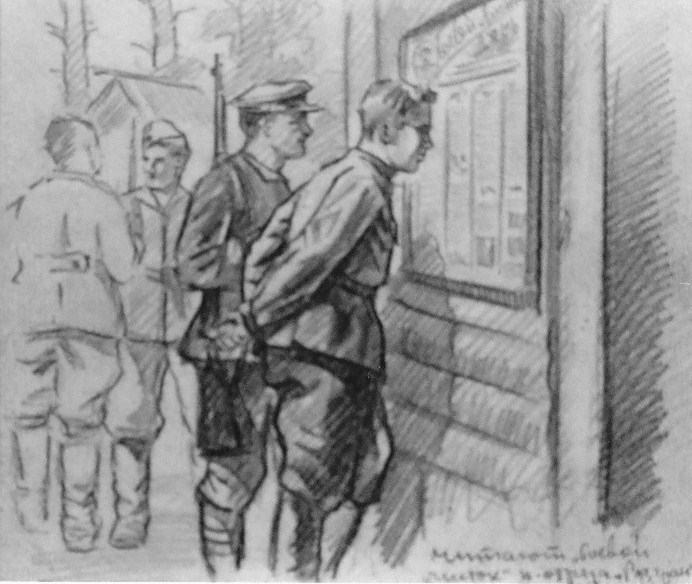

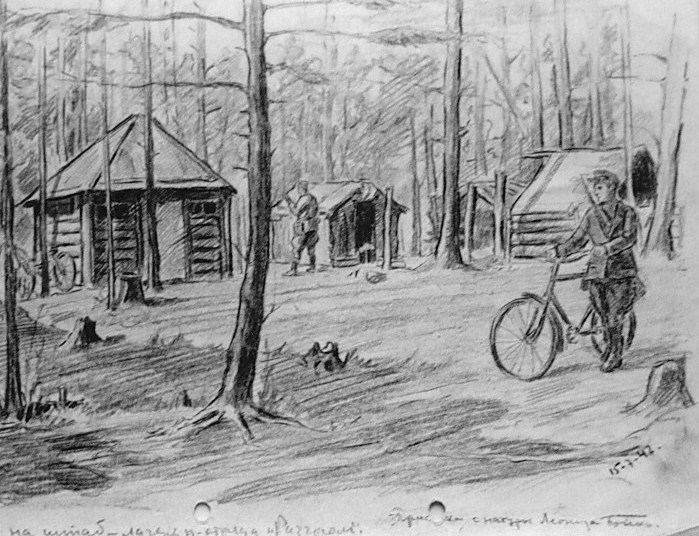

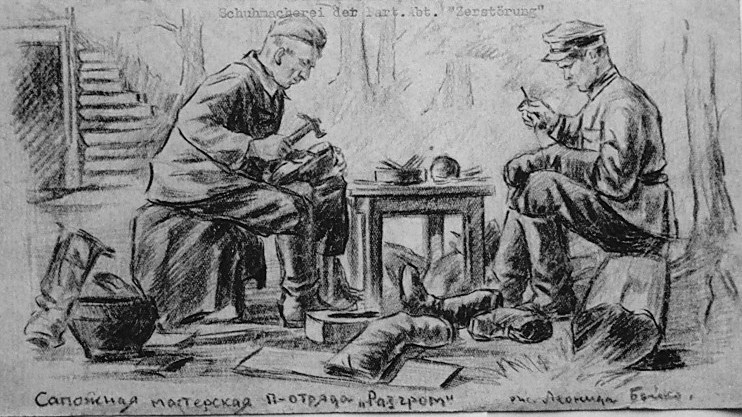

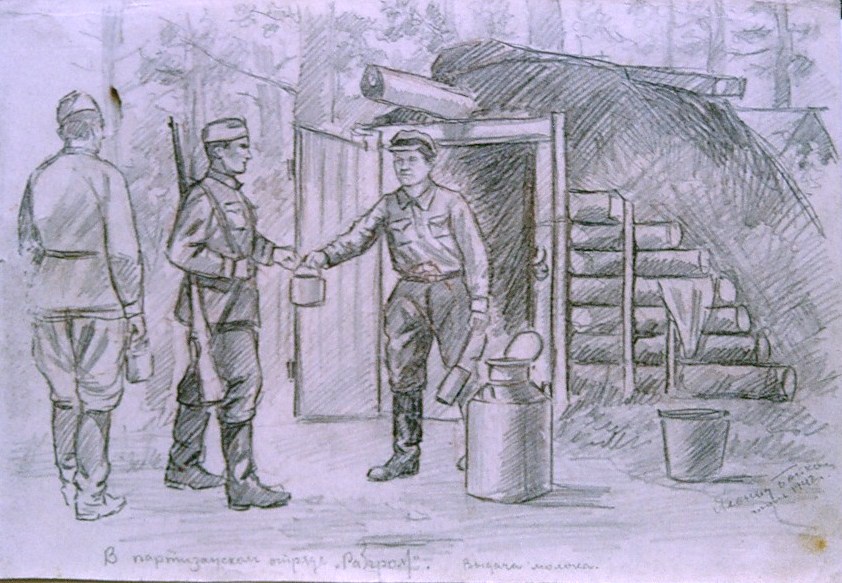

When Prof Kwiet and I were going through the archived documents in the Prague archive in 1990, I came across a collection of sketches and drawings made by the Partisans. Obviously these had been captured by the Nazis. I photographed some of these photos.

I hope you find this blog interesting.