Richard Letchford, who we all lovingly referred to as ‘Dick’ had prepared a chapter for the book ‘Nazis in Australia’, however, it did not survive the editing process. What follows is the main thrust of his contribution.

Dick Letchford was a former Detective Inspector in the New South Wales Police and retired after 38 years of service. In 1983 he had been in the NSW Police for 16 years when, as a Detective Sergeant, he was seconded to the Stewart Royal Commission, which was investigating organised crime associated with the Nugan Hand Merchant Bank. Dick remained there for two and a half years until 1985. The Royal Commission led to the creation of the National Crime Authority and from 1985 he was seconded to that organisation for two years until 1987.

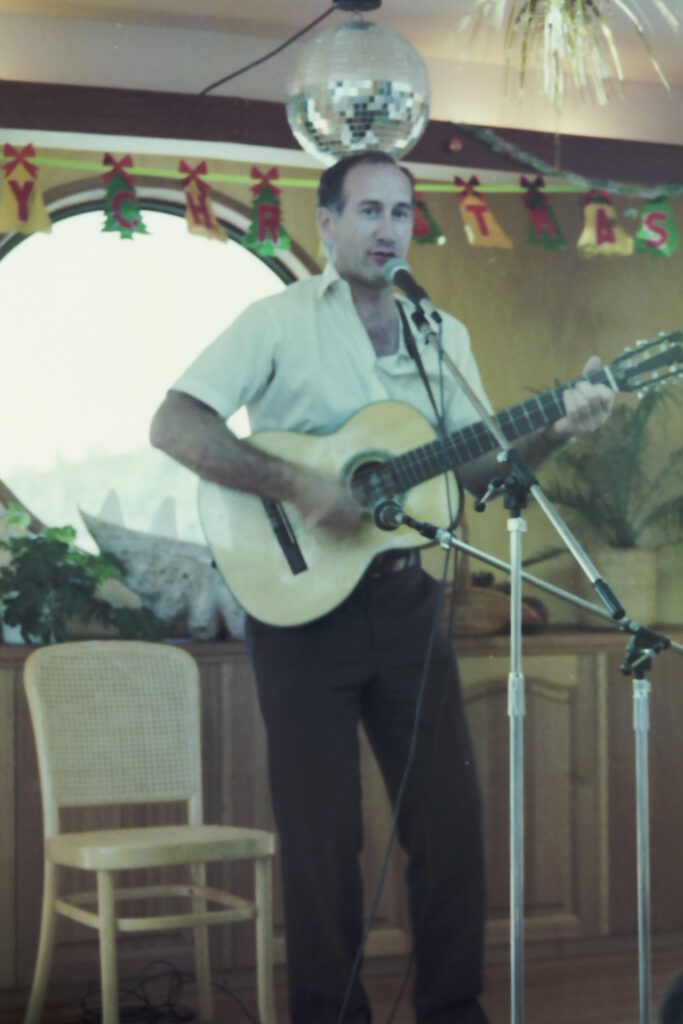

Dick Letchford entertaining staff at the 1986 NCA Christmas Party

In 1987 he was seconded to the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) of the Federal Attorney-General’s Department.

Like others, Dick recalls at the end of the World War II some alleged war criminals entered Australia, the United States of America, Canada and the United Kingdom. He recalls, it appeared some were turned into counterintelligence agents and most were never investigated or prosecuted for their involvement in Nazi war crimes. Notwithstanding, Dick said he was satisfied there was no ‘hidden agenda’ in relation to the creation of the SIU and its work, in fact similar initiatives were being pursued in other western countries, including the USA, Canada and the UK.

He recalls, in the early 1950s the Soviet Union, sent a request to Australia for the extradition of a high level Nazi, Ervin Viks, even providing his residential address in Campbell Street, Sydney. It was apparent Soviet intelligence agents were operating for some time in Australia and were conducting their own investigations. The Australian Attorney General at the time, Sir Garfield Barwick, continued to reject the request for the extradition of Viks, claiming inter alia the USSR and Australia did not have an extradition treaty.

Viks along with two others, Juhan Juriste and Karl Linnas, were accused of murdering 12,000 people in the Tartu concentration camp in Estonia. That number was revised down to 3,500 people and included mainly Estonian citizens, including Estonian Jews as well as some Soviet POWS. Linnas and Viks were tried in absentia in Tartu and sentenced to death.

Viks was born in Tartumaal, Estonia in May 1897 and migrated to Australia from London, arriving by ship in Fremantle on 15 August, 1950 with his wife Salme, who was then 45 years old. Both he and his wife later moved to Kendall Street, Concord, NSW. Viks died in April 1983, before the SIU was established, and was buried at Rookwood Cemetery. Details of the SIU’s investigations involving Viks are set out on pages 209-216 of the final SIU report.

Dick recalls that from what he understood, the Soviet Union had reminded Australia during some trade negotiations that Australia had affirmed the 1943 Potsdam Agreement, which among other things provided for the prosecution of Nazi war criminals. In particular the agreement set out certain actions to be taken at the conclusion of the war, namely the total disarmament and demilitarisation of Germany; the territorial division of the country into occupational zones to be controlled by the Big Three (the UK, USA and the Soviet Union) and France; and, most importantly, the prosecution of persons who committed war crimes.

During 1987 and 1988 Dick was actively involved with SIU investigators Gray and Jansen in identifying and locating suspects and persons of interest. Of the 20 primary SIU suspects at the time, Dick, assisted by Gray and Jansen, located eight of them.

Dick recalls suggesting to Bob Greenwood, the SIU Director, that an investigator should be tasked with regularly checking on the Unit’s suspects, as they were old or infirm and could die whilst investigations were being undertaken. However, this suggestion was not adopted as the SIU did not have the resources to mount such a surveillance program. As it turned out, in one instance the SIU did waste significant resources investigating one suspect, Wladyslaw Stankiewicz (PU 21), who was first located during the course of the Menzies Review living in Sydney, NSW. He died in early September 1988.

Stankiewicz was alleged to have been involved in the murder of people in his home village in Poland. After he died, and before the SIU became aware of his death, investigations were undertaken in Israel commencing in September 1988, when Dick’s team had spoken to a number of persons seeking evidence regarding Stankiewicz’s involvement in the killings of people in Kurzenice, Belorussia (now Belarus).

In February 1989 Dick travelled to Israel with Investigator Bill Beale to gather evidence regarding the SIU’s Lithuanian investigations and also relating to Stankiewicz. In July 1989, whilst on a second mission into Belorussia, Dick was gathering further information on Stankiewicz, when advice was received to cease any further inquiries as Stankiewicz was deceased. Dick was not told of the date of his death, but later found he died in early September 1988.

During this mission to Belorussia and prior to being advised about the death of Stankiewicz, the Russian Procurator (Prosecutor) had arranged for the SIU team to visit the town of Kurzenice, where Stankiewicz was alleged to have been involved in the murder of some of the villagers. Dick recalls that on arrival, it was like stepping back in time to the early 1900’s. Part of the Jewish Synagogue was still standing, but it had been burnt out, and a large tree was growing out of the ruins. In the main street was an old hand siphon pump and he watched as women of the village came with buckets to fill for their home use. He found it very depressing, and thought, how lucky we were in Australia to have the facilities these people never had.

Over his two-year secondment to the SIU, Dick travelled with other investigators to Israel, Hungary, England, Poland, USA, Canada, Yugoslavia (Sarajevo, Split and Belgrade) and the Soviet Union (Moscow, Lithuania and Belorussia), gathering evidence.

Whilst in Latvia he carried out investigations in Riga where his team interviewed men who had been prosecuted by the Soviets for being Nazi collaborators and who had been sentenced to terms of imprisonment for their actions during the time of the German occupation. The team went to WWII execution sites near Riga and Liepaya, were Jews had been rounded up at the fire station and executed. Others were taken to the beach and shot with their bodies being buried in trenches in the sand. Dick was shocked at the number of sites around the country where people had been executed.

In Riga, the SIU team were taken to one site in a forest, where they saw mass graves of many people who had been slaughtered. In Belorussia they visited other execution sites and mass graves. The one that really stuck in his mind was in Minsk during their mission in July 1989. During the war the Germans entered a small village, rounded up all the Jews and pushed them in to a barn and then set fire to it, shooting anyone who attempted to escape. All occupants perished. The Soviets built a memorial on the village site, erecting chimneys where each house had stood. There was a bell in each chimney tower which rang in sequence in memory of those who had been murdered. Another feature of the war memorial was a tall statue of a man holding his dead son.

Dick recalls an occasion in Moscow watching TV, and even though he couldn’t understand anything being said, it wasn’t too hard to understand what was going on. The Russians were constructing a roadway through a forest, when they opened up a number of mass graves. He wondered whether this is what happened to the Soviet prisoners of war who had been captured by the Germans and later repatriated to Russia by the British and Americans at the end of WWII. Thousands of these repatriated POWs were executed by Stalinist forces and buried in mass graves throughout the Soviet Union. Stalin told the allies no Russian soldier would surrender and would rather die fighting.

On 25 August 1989, Dick finished his secondment at the SIU and returned to the NSW Police Force. It took him some time to readjust to what one could call normal life.

Whilst carrying out investigations at the SIU, what really stood out his mind was man’s inhumanity to man. Now today he looks back at the similar atrocities committed around the world in Africa, the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia in particular), Ukraine and Gaza, just to mention a few, and realises nothing has changed since the end of the Second World War and centuries before. He thinks to himself it was all a waste of bloody time because humanity never learns.