NAZIS IN AUSTRALIA

There is an area of Australian legal history which, outside academic circles, remains largely unknown to current generations of Australians. It is not taught at schools or universities but is an area that should generate pride in anyone interested in the rule of law and bringing war criminals to justice.

Having regard to President Putin’s illegal war in Ukraine and the countess war crimes being committed there on a daily basis, the topic of prosecuting war criminals is important for anyone interested in maintaining the rule of law in free and democratic societies.

For this reason Australia’s attempts to bring Nazi war criminals to justice is an important part of Australia’s legal history and is deserving of a higher profile than it currently enjoys.

Towards the end of the Second World War as Hitler’s Third Reich was crumbling and when the Soviet Red Army was advancing westward towards Berlin driving the Nazis occupiers before them, thousands of Nazi collaborators and sympathisers retreated westward to avoid what they believed would be well deserved reprisals and repercussions for their involvement in war crimes committed during years of Nazi occupation.

The result of this westward migration resulted in hundreds of thousands ending up in displaced persons camps in Western Europe. At war’s end there were tremendous efforts made to resettle these displaced persons in many countries around the world. Australia was one of these countries that was prepared to accept thousands of these displaced persons. Other countries participating in this process included Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, France, Israel and several South American countries.

Amongst the genuine refugees, however, were Nazi collaborators. In the chaos of the time they were able to blend in and were willing to deny any collaboration with the Nazi when they were being processed for resettlement to countries prepared to take them. Thus it was not surprising that as time passed, it started to become apparent that there were war criminals amongst the genuine refugees who were allowed to settle in the welcoming countries.

Australia was not immune from this phenomenon. It didn’t take long for genuine refugees to identify their persecutors living amongst them freely in this country. Reports that war criminals were walking our streets were received by the governments of the day and the Commonwealth Police. Whilst some investigations were undertaken the reality was that nothing was done to prosecute these alleged war criminals. The main political attitude and goal in Australia during the late 1940s and 1950s was the country should “populate or perish” and should move on from the evils of war, letting by-gones be by-gones.

It is apparent that in some instances the Australian authorities, including ASIO, were aware of the presence of war criminals in this country and indeed relied on them to help counter the perceived threats posed by expanding communist regimes to our north. Other democratic countries were guilty of the same behaviour.

Whilst there were some inconclusive war crimes investigations undertaken in the 1950s, at the same time the Australian government received several extradition requests for known war criminals to be arrested and expelled to face war crimes charges in countries such as the Soviet Union. Australia would have no part of this and in 1961 the Attorney General of the day, Sir Garfield Barwick, announced that the chapter of prosecuting war criminals in Australia was closed.

However, ABC investigative journalist Mark Aarons was able to prise the chapter open in mid-1986 when, after almost a decade of thorough investigations, several of his Background Briefing programs were broadcast revealing that there were indeed “Nazis in Australia”.

The programs hit a lot of nerves. There was a huge public reaction to the programs, calling for action. The Hawke Government was prepared to respond in a positive way. The end result was to create a Special Investigations Unit (SIU) in April 1987, headed by Bob Greenwood QC. His mandate was to investigate all allegations involving Nazi war criminals living in this country. If there was sufficient evidence, he was to prepare briefs of evidence which would be submitted to the Commonwealth Director of Prosecutions (DPP) for the preparation of an indictment. The ensuing prosecution would take place in the Supreme Court of the State where the indicted accused resided. The accused would face trial before a judge and jury, as required by the Australian Constitution. In tandem with the creation of the SIU, the Australian War Crimes Act of 1945 was amended to enable such prosecutions to take place.

After extensive investigations the SIU did present four cases to the DPP for prosecution. The first involved a man named Ivan Polyukhovich, a former forest warden who collaborated with the Nazis when they occupied the Ukrainian village of Serniki where he lived. It was alleged he was involved in several murders and participated in the mass execution of almost 1,000 people, the Jewish population of Serniki in August/September 1942. Polyukhovich was indicted in January 1990.

Following an unsuccessful High Court challenge by Polyukhovich’s legal team relating to the constitutional validity of the amendments to the War Crimes Act of 1945, his case proceeded in the courts in Adelaide, resulting eventually in his acquittal by a jury in May 1993.

The second person indicted was Mikolay Berezovsky who was arrested in September 1991 for his involvement in the mass execution of over one hundred Jews from the Ukrainian town of Gnivan in mid-1942. His court proceedings concluded in July 1992 when he was discharged by a Magistrate in Adelaide.

The third and final person indicted as a result of the SIU’s investigations was Heinrich Wagner. He was arrested by the SIU in September 1991 and was indicted in respect of his involvement in the mid-1942 murder of 104 Jewish adults and about 19 children who lived in the village of Izraylovka in Ukraine. Wagner was to stand trial in the Supreme Court in Adelaide in 1994 but the DPP terminated the proceeding in December 1993 when Wagner suffered a non-fatal heart attack.

The fourth case presented in June 1992 to the DPP by the SIU did not result, for political reasons, in an indictment of the man Karlos Ozols who should have been indicted for his involvement in the mass murder of tens of thousands of Jews in Minsk, Byelorussia.

Following the termination of the Wagner case the SIU closed its doors permanently in February 1994. It was a positive development when, because of their expertise, many SIU (and DPP) legal and investigative staff were recruited by International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) based in The Hague commencing in February 1994.

In the three cases that did result in indictments, a main feature of the SIU’s investigations was the exhumation and forensic investigation of the bodies of the murdered Jews in the mass graves located in Serniki, Gnivan and Izraylovka. Valuable evidence was gathered during the exhumations and the expertise gained in the process was later put to use when the ICTY carried out mass grave exhumations in Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo.

The SIU presented a report to the Federal Government in September 1993 detailing the results of the 841 individuals investigated by the Unit. An online copy of the ‘Report of the Investigation of war criminals in Australia” is available on the Australian Government Publishing Service website.

I am currently putting the finishing touches to a book which when published, will provide important insights into the full background of the SIU. The contributors to the book include the investigators, historians and lawyers (including the senior counsel for the three defendants) who were involved in the process. I will announce on this website when the book is published, probably in 2024.

Mark Aarons has written the Foreword to the book in which he states: “Despite not achieving one conviction, the professionalism and tenacity of the men and women of the Special Investigations Unit who belatedly attempted to bring to justice men who had been part of the worst genocide in human history deserve our thanks. Without their extraordinary efforts Australia would be a pariah in the international community as the only Western democracy not to have made an effort to erase the blight of our past indifference toward Hitler’s mass murderers living freely among us and the culpability of our political leaders in turning a blind eye to their presence here. Australians can be proud that we have such dedicated, moral people as those who served in the SIU.”

Bob Greenwood QC, Director of SIU, in Rovno, April 1990.

Serniki mass grave, December 1992 where the Jewish victims were exhumed by the SIU in July 1990.

Orthodox Church in Serniki village in December 1989.

Graham Blewitt with two Rovno Procurators in Rovno April 1990.

Minsk July 1989 – Statue of “The Unconquered Man” in the centre of the Khatyn Memorial Complex, depicts a man holding the body of his dead son.

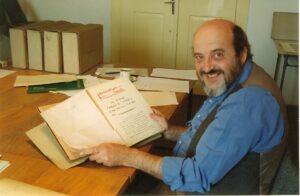

SIU Chief Historian Prof Konrad Kwiet undertaking research in archive in Prague, March 1990.

SIU staff carrying out archival research in Brest, Belarus in December 1992.