Professor Ludmila Stern is an interpreting scholar at the School of Humanities and Languages, UNSW Sydney. She had been an interpreter/translator with the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) and has contributed a chapter for the book Nazis in Australia – The Special Investigations Unit – 1987-1994. The contents in this blog do not appear in the book. Ludmila is a good friend and she has provided the information that I have included in this blog.

Ludmila’s contribution to the book dealt with Australian war crimes investigations through the eyes of an SIU interpreter and she dedicated her chapter to the SIU’s interpreters and translators.

Ludmila commenced her contribution with the following quote by Helen Elias-Bursać (2014): ‘Translation and interpreting do more than just facilitate the proceedings. They shape them.’

At the end of 2000, Ludmila visited the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague. I was able to facilitate this visit, the first among many more to come, in my role as the ICTY Deputy Chief Prosecutor and the former SIU Director.

Ludmila visited the ICTY with the aim of observing the war crimes trials relating to the conflicts committed during the 1990s in the Balkans and to find out how the Tribunal communicated with witnesses and defendants from the former Yugoslavia. By all accounts, and later from her observations from the public gallery, she concluded that multilingual communication via simultaneous interpreting went smoothly. She was curious, given her experiences at the SIU, about the Tribunal’s interpreting practices and the ways its lawyers and judges managed the evidence despite the witnesses coming from cultures different from those of the Tribunal and didn’t speak its official languages, English and French.

Her curiosity as a researcher in these matters was piqued by the recent, far less successful, experience of the Australian war crimes prosecutions (1986-93) involving witnesses from the former Soviet Union. She had been involved with the SIU as an interpreter and translator from 1989 until 1993.

In providing the information for this blog, Ludmila recalls the work and some of the experiences of the SIU interpreters and translators whose contribution was essential in the course of the investigations. The picture she presents is not comprehensive as it only includes the perspective of those colleagues whom she managed to reach and her own experience. While reiterating that some of the facts are described in greater detail in other pieces of her writing, they will be presented from the linguistic and cultural angle that will explain its impact on the investigations and, later, the court proceedings.

In December 1989, Ludmila was completing her first year as a part-time Russian language instructor at UNSW while also working as a free-lance Russian/English interpreter and translator, and SBS subtitler, accredited by NAATI (National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters). Her mentor and colleague, Michael Ulman, spoke to her about the opportunity to do some work which he described as being of ‘an unusual nature’. Ludmila found the offer a bit vague but nevertheless intriguing, and without asking any more questions, Ludmila agreed to approach the SIU.

Today, thirty years later, Ludmila still vividly remembers the SIU office in a high rise building in King Street in Sydney CBD, within walking distance from the Harbour Bridge and the Rocks, with no signage at the entrance to indicate what organisation she was about to join. Inside, the open plan office looked plain, with only a few offices. After a brief interview it was explained to her that the office investigated war crimes allegedly committed during WWII on the territory of the Soviet Union by some Nazi collaborators who, after the war, found refuge in Australia; she was being offered the job as a casual translator.

Unlike other international organisations and courts, in Australia an in-house translation and interpreting (T&I) unit was rare, with, perhaps, the exception of the SBS (Special Broadcasting Service) Subtitling Unit. Some of the SIU’s translators were found through the NAATI directory, others like Irene Ulman and Eugene Ulman, Mira Grinberg, Tanya Ryvchin and Ludmila, were recommended by other SIU staff, others like Edytta Super were found through SBS.

Some languages encountered by SIU, required teams of three or more translators, and during very busy times they would increase to up to five, as was the case with German, and seven, in Russian. Translations in those pre-internet days were written out by hand, later to be re-typed on a word processor by the SIU admin staff. There was a library with reference materials and dictionaries. For a free-lance who was used to working alone, mostly translating from home, Ludmila found working as part of a team was a novel experience. She discovered it was good to interact with colleagues and consult lawyers and investigators for advice and opinions. The T&I team members came from different ethnic and professional backgrounds, and most of them were native speakers of the relevant languages.

In the office, Russian-speaking translators, including Ludmila, translated official documents such as memorandums of understanding, official correspondence, and archival war-time and post-war documents. These included Soviet Army officers’ official reports the on state of the areas liberated by their military units, with graphic accounts of Nazi atrocities and destructions, and numerous Soviet minutes of interrogations (protocoly doprosov) of witnesses and accused during post-war trials. The latter interviews were conducted by KGB officers who interrogated Nazi collaborators – local police (politsai) and village elders (starosty).

Ludmila recalls “The question the translators often asked themselves was whether to remain faithful to the original style developed under both the Nazi and the Soviet regimes, that would sound odd in the English translation, or adapt it so as to bring the language of the translations closer to the understanding of the Australian investigators and lawyers, making them sound more familiar and acceptable for the use in Australia. In the absence of any guidance in such matters, professional or academic, and well before Laurence Venuti’s theory of ‘domestication’ and ‘foreignization’ of translation (The Translator’s Invisibility 1995) became known, we discussed these and other problems among ourselves”.

Ludmila has also noted “it came as a surprise to most of us when we found out later that translation work would alternate with interpreting and that we would have to travel interstate and overseas. For instance Eugene Ulman, initially an SIU Russian translator, was somewhat caught by surprise when he was told he would be accompanying the investigators to Ukraine at the end of 1989.

“Interpreting during overseas assignments was complex, with topics ranging from informal daily ones to formal high-level negotiations. Graham Blewitt remembers that while overseas, interpreters allowed SIU staff to communicate with officials, witnesses and survivors, but also to interpret menus and to order the team’s meals. In Eugene’s case, interpretation was required from the moment the British Airways plane landed in Sheremetevo airport in Moscow, then throughout all stages of the mission, which included the talks with the officials at the Prosecutor-General’s office in Moscow and the regional prosecutors in Ukraine and later interviews with witnesses. When writing in English, the Soviet prosecutors called themselves ‘procurators,’ the word being a calque of the Russian prokuror, or ‘prosecutor’ in the Roman law system. The humour of this translation was that it had no meaning for the speakers of Australian English. The name, however, stuck and no one in the SIU ever called the Soviet prosecutors anything but ‘procurators’ ”.

Working as an interpreter at the SIU took Ludmila several times to Moscow, but mostly to Ukraine: to Rovno and Serniki (in the Polyukhovich case), to Kirovograd (in the Wagner case) and Vinnitsa (in the Berezovsky case), and also to Kiev (now Kyiv). Her first mission took place in April-May 1990, during the period that was marked by post-perestroika turmoil and unprecedented political changes. While the central Moscow authorities continued to be supportive of the SIU’s work, these investigations took place at a time when the USSR was on the verge of collapse, triggering a domino-effect throughout the Eastern and Central Europe. In 1989 – 1991, the Soviet republics, one by one, declared their independence, with Ukraine seceding in 1991.

Ludmila (centre) next to me on the left and Kiev Procurator Vasily, Abramenko on the right

Ludmila reflects that it would have been impossible to conduct the investigations without the approval and support of the Moscow-based Office of the Prosecutor-General of the USSR, the high-level agency that ensured the support of the authorities in the regions. These regional prosecutors’ offices helped identify witnesses, encouraged them to testify and provided venues for the witness interviews. In addition, the Rovno prosecutors’ office provided local Russian and Ukrainian speaking interpreters to speed up the interviewing process. It turned out to be helpful also because the local population in that area didn’t speak a standard Russian but a local variation of Ukrainian mixed with Russian, commonly known as surzhik.

Ludmila with local Rovno interpreter Stas Kostetsky

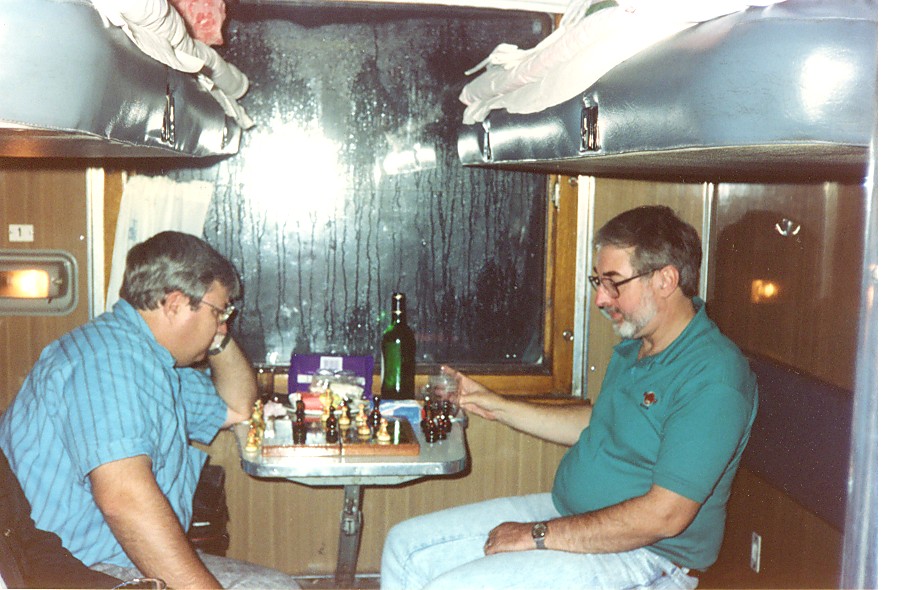

Ludmila has said “In April/May 1990 during our 24-hour train trip to Rovno where Graham Blewitt (no Aeroflot flights for Graham after his earlier experience!) played chess with the counsel for the prosecution, Greg James QC, I helped to communicate in a rather leisurely exchange with the train attendants about bed linen, tea and meals. In Rovno, in the morning I would be interpreting menus and ordering the food in the hotel restaurant, and the during the working hours interpreting during semi-official discussions at the regional prosecution office, and in the evening during conversations and toasts that were parts of numerous meals. In the village of Serniki where the local Jewish population (‘Soviet civilians’, to quote the Soviet euphemism) had all been shot and buried in a pit, I interpreted, standing inside the freshly exhumed mass grave, explaining the details of the 1942 mass execution, slowly walking along the 850 remains of local Jews, mainly old people, and mothers with children.”

Greg and Graham playing chess during the rail journey from Moscow to Rovno

Ludmila (far right) on her mission to Rovno in May 1990 with (from right to left) me, Greg James, Natalia Kolesnikova (Moscow based Senior Prosecutor), Stas Kostetsky and SIU Director Bob Greenwood.

Ludmila continued “The local hospitality included taking foreign delegations to places of interest. Memorable was the visit of the estate of the famous 19th century military surgeon, Dr Pirogov, outside Vinnitsa, with his body on display, embalmed according to his own recipe. Interpretation went on, non-stop, in restaurants and offices, and I gratefully remember Tania Ryvchin taking over during an excursion to some local museum and later a local restaurant.”

Occasionally, during these overseas missions, a written statement or a document had to be translated with great urgency, for example, when the team was on its way to a formal meeting with high-level officials. Ludmila recalls this was done on the back seat of a car, often with her scribbling on some scrap of paper.

Satisfyingly (for me), Ludmila also recalls “one of the highlights of our interpreting work at the SIU was that we felt part of the team of investigators and lawyers, especially when travelling overseas. This remarkable inclusive attitude did not start immediately, and initially interpreters and translators were not always briefed by interpretation users which left them with little understanding of the aims of the investigation.”

As the increasing number of overseas missions produced a growing number of audio and video recorded witness interviews that had been interpreted by local interpreters, back in the office the translator’s task was to double check the interpretation. The purpose was to verify the accuracy of the original interpretation in the field, making corrections wherever necessary, and transcribe these interpreted interviews accurately in correct English.

I am proud of Ludmila’s observation that “as we checked these audio-recorded witness testimonies, we interpreters and translators observed, time and time again, how professionally skilled the SIU investigators were: Bruce Huggett, Bob Reid and John Ralston stood out. My colleagues Mira Grinberg and Tania Ryvchin made the same observations about the investigators they had worked with, Keith Conwell and Paul Malone. Having come to the SIU from NSW and AFP police, they all worked in unchartered territories of international war crimes investigations, in a foreign environment, within a different political system, with witnesses who had different expectations of the legal process and a unique way of expressing themselves even in their own languages. And yet, even though the witnesses often had to testify in the intimidating environment of the prosecutor’s office, through an interpreter, the SIU investigators managed to establish a rapport with them, earn the witnesses’ trust through their openness and professionalism, and get them to recount their traumatic war-time memories, and later testify in a foreign court.”

SIU interpreter Mira Grinberg – at the site of the mass grave in the case involving Henrich Wagner

Ludmila also recalls “as we heard in the audio-recorded witness interviews, the investigators asked concrete factual questions in such ways that they triggered the witnesses’ recollections; they were flexible in their interviewing techniques, changing tactics when necessary. They promptly detected inconsistencies and even interpreting errors that distorted the testimony (was it 15 km or 5 because the original 15 km made no sense?). It is true that the witnesses (and the Soviet prosecutors) failed to understand why foreign investigators questioned them about the facts that in the USSR was general knowledge and an official version of history. They failed to understand why their accounts, based on the local memory and their lived history, wasn’t good enough – didn’t everyone in the village know that Ivancechko the forester collaborated with the German police, and therefore was guilty of murders by association? Nonetheless, they responded to the questions about what they had seen, what colour was Ivanechko’s jacket and the kind of weapon he carried – in detail and cooperatively. This approach to unearthing information using investigators’ facts-based interviewing strategy was later adopted by those interpreters who pursued research or journalism involving human interviews.”

When the court hearings began, and when foreign speaking officials and witnesses arrived in South Australia, it was again necessary to seek the assistance of SIU interpreters. Mira Grinberg, Irene Ulman, Tanya Ryvchin and some other SIU interpreters spent weeks at a time away providing support and assistance to Ukrainian witnesses, many of whom had never left their native village before.

Soon after the first committal hearing, that of Polyukhovich, began, the South Australian Deputy DPP, Grant Niemann, raised the alarm, saying that the case was crumbling, and that ‘something to do with language’ was undermining the evidence. It is important to note that the SIU interpreters, who were familiar with the cases, were not allowed to interpret during the proceedings. Those court appointed interpreters who were called to interpret in court, as is the case today in domestic courts in most Australian jurisdictions, received no briefing and were given no background to the cases. Even today the former SIU interpreters hold conflicting views as to whether Russian and/or Ukrainian court interpreting contributed to communication problems that unexpectedly arose in court, some believing that the interpretation by court interpreters was accurate, whereas the others point to inaccuracies of content and style in the court transcript, including style editing and raising the register of the witnesses who spoke colloquially.

Following Grant Niemann’s observations, Ludmila was asked to examine the court transcripts to try to identify the root of courtroom communication problem – an assignment that marked the start of her work as a linguistic researcher. However, the court transcripts of the committal hearings were available in English only, with the highlights pointing to areas of miscommunication or even communication breakdown, leaving her guessing from the English transcript what the Russian/Ukrainian original could have been, trying to understand what had caused the miscommunication. As SIU Director, I was able to have Ludmila’s analysis of the linguistic situation tendered into evidence, as an expert report (Linguistic Report in the War Crimes Prosecution of H. Vagner, 1992), to draw the judicial officers’ attention to communication problems, first in the Polyukhovich proceedings, and later in the Wagner case.

Ludmila asked: “To what extent were language and other associated problems due to interpretation? The problem of evaluating non-English speaking witnesses from a distant culture had been highlighted in several Australian reports. According to Sir James Gobbo of the Supreme Court of Victoria ‘while judges often found particular witnesses were truthful and impressive, this was rarely said of witnesses whose evidence was given through an interpreter, as such evidence often lost all impact’ (Access to Interpreters in the Australian Legal System. Report. Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department. April 1991, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, p. 45). This 1991 Report was critical of those judges who tried to determine ‘whether the witness is telling the truth through an assessment of a witness’s demeanour.’ It concluded by saying that ‘this approach frequently leads to misinterpretation of the behaviour and reactions of people who come from a different culture by those who are not aware of such differences’. In 1991, Susan Berk-Seligson’s seminal work The Bilingual Courtroom: Court Interpreters in the Judicial Process had only just been published, and her insights demonstrating the impact of interpreting on the evidence had not yet received the resonance it gained later. All of the above has proven relevant to the Australian war crimes proceedings.”

Ludmila has noted “the transcripts provided a great variety of examples of how interpreted communication, when handled without adequate understanding, can damage a case. Some striking examples show how the mix of Russian and Ukrainian could cause confusion: whereas vsekh pobili which in Russian means ‘they were all beaten up’; in the local dialect of Ukrainian vsikh pobyly meant ‘they were all killed’, potentially leading to misinterpretation. Other examples showed how the use of poorly structured lengthy questions with embedded sub-questions, asked by counsel in one go, without pauses, could easily lead to omissions and misinterpretations:

Q: Do you remember him asking you this question, and this was a question that Mr Malone asked you, and he was reading from the statement that you’d given Mr Podrutskiy before, and he said this, ‘I’m reading from our translation of your previous protocol from 1987 and it states “when I saw Granovska I heard that she was asking the policeman who was guarding the column – she said her husband was Russian”.’ […] And instead of answering her, the policeman beat her with the lash and also beat the child.’ Is that correct? (Taken from the Berezovsky committal hearing transcript).

However, although sometimes the witnesses clearly misunderstood a question, either because they were poorly phrased or because of interpretation, they would not admit to it. Ludmila observes this is ‘gratuitous concurrence,’ that is, agreeing with any statement by a person in a position of power, and now well known in interpreting literature (e.g., Diana Eades) was a common feature shown by witnesses from both cultures.

Ludmila recalls “as I said, apart from the English-language transcripts there was no Russian/Ukrainian audio recording to verify whether the interpretation maintained the accuracy and the intention of these questions when interpreted to the witnesses, however, in some cases witnesses indicated difficulties understanding the prosecution’s open-ended questions in the examination in chief:

Q: Was there a time after that when the Germans came?

A: In which time? I don’t understand.”

“In cross-examination, persistent repetitive questions, with variations in their phrasing ever so slight that they would not have a ready-made grammatical equivalent in languages other than English, caused a hostile reaction from witnesses and even the retraction of their earlier statements:

Q: Had you seen him before the occasion that you saw the Jews led into the pit.

A: No, I did not see. Did not see. Did not see. (…)

Q: So you had seen him before that day that you say you saw him at the pit.

A: No, I did not see.

Q: But you told us you saw him at his wedding.

A: That was in 1940 as he was getting married.

Q: I’m not talking about on that day. I’m talking about before that day.

A: I did not see. I did not know him. Up until that time I did not know him. (…)

Q: To be absolutely fair and clear, I’m talking about occasions you’ve seen him before that day, not on that day.

A: I did not see. (…)

Q: Before the day the Jews were killed.

A: I did not see. I did not see.

“Unfamiliar examination strategies, for example referring witnesses to their earlier statements, caused additional comprehension difficulties, further exacerbated by the playing of a video–technology previously unseen by the witnesses:

Q: What did you just say on television then.

A: I can hear what I had said, but I do not remember saying that. Neither had it entered our heads.

Q: And tell again what you said.

A: Where?

Q: On the television that’s just been played.

A: Do I remember what I said then?

Q: Tell us what you just heard.

A: I did not look closely, I did not see.”

These and many other types of communication problems, leading to misunderstandings and communication breakdown, were also present in Wagner’s committal hearing, where the SIU again wanted the Magistrate to read the report to gain a better understanding of the nature and process of interpretation. The Magistrate did not accept Ludmila’s report being tendered as an expert witness report, however, he agreed to read it and referred to it, when communication difficulties occurred.

I hope the contents of this blog sheds some light on the important but difficult tasks that confronted the SIU interpreters and translators, who completed their professional tasks with distinction. I am very grateful for the tremendous contribution my friend Ludmila and her colleagues made to the outstanding achievements of the SIU.