ROBERT (BOB) FRANCIS GREENWOOD QC

(1941 – 2001)

The purpose of this blog is to pay tribute to and acknowledge the important role played by Robert (Bob) Greenwood QC, who more than anyone else, has put Australia on the world map when it comes to investigating war criminals.

Bob Greenwood led the way without precedent when creating the Special Investigations Unit in 1987. His task from the Hawke Federal Government was to investigate allegations that there were Nazi war criminals living in Australia, with a view to bring criminal prosecutions in the courts of Australia.

He had little support in this country for this noble endeavour, one which many said was doomed to failure. He often faced obstacles and criticism performing this task, yet on each occasion he rose to the occasion and produced successful results. He was not a person to be messed with. He proved the critics wrong, when they said there would never be any prosecutions flowing from the work of the SIU.

Sadly Bob died on 21 October 2001, at the age of 60.

Towards the end of this blog I have set out Bob’s official obituary, as well as an address delivered by Mark Aarons at Bob’s memorial service following his death. Those testimonials set out many important aspects of Bob’s life and his endearing character so I do not propose to repeat them here.

Rather I will focus on my relationship with Bob.

THE NATIONAL CRIME AUTHORITY

I first met Bob in January 1986 when I was working at the National Crime Authority (NCA) in Sydney. The specific details of our professional relationship at the Authority are set out in my book ‘Justice and War Crimes’. Briefly, Bob was appointed for a twelve month period as an Acting Member of the Authority and was given responsibility for the conduct of the ‘Silo Reference’, in respect of which I was the team leader. ‘Silo’ was a dynamic investigation, having commenced in June 1885, and in part involved the arrest and extradition of the two main suspects from London and Innsbruck/Vienna during 1986.

The main target of the ‘Silo’ reference was Bruce (Snapper) Cornwell who was arrested on an NCA warrant in London on 7 November 1985. Following his arrest, immediate action was taken to have him extradited to Sydney. Some legal obstacles arose during the extradition process and Greenwood and I were required to travel to London on a number of occasions to assist in the process.

Cornwell had acquired the nickname ‘Snapper’ because he was a slippery customer when it came to evading the police. He had amassed a financial fortune due to his drug importation activities, and it was feared he had the means to arrange his escape en route while being transferred back to Australia.

To overcome this potential embarrassment, Bob Greenwood, arranged for Cornwell to be escorted from London to Australia on an RAAF jet aircraft – rather than on a commercial plane. This was only one of Bob’s unusual and unprecedented manoeuvrers and achievements. It was my understanding that long after Cornwell was safely escorted back to Sydney, there were extensive and protracted discussions and disagreements about who was responsible for paying the cost for this exceptional extradition travel.

There was a period during 1996 when Bob was moving his family’s residence. He had a large family and this was before the day when modern family size motor people movers were available. To transport his family around, Bob owned a white stretch Mercedes vehicle. When he was moving house he asked me to garage the vehicle temporarily at my residence, as he had nowhere to park it safely. I agreed, with pleasure. He asked me to drive it around each weekend to keep it in good working order. To say the least my children were delighted to be chauffeured around in the stretch Mercedes – it certainly turned heads in our neighbourhood and at my parents place when we visited each week.

I was extremely disappointed at the end of 1986 when Bob’s 12 month contract with the NCA was not renewed.

NCA Christmas function – Sydney Harbour boat cruise – 19 December 1986 – Bob Greenwood, far left with can of Fosters beer in hand.

After the Christmas lunch aboard the boat, Bob Greenwood was in full voice with NCA Chairman, Justice Don Stewart.

Bob loved to sing, in particular Irish ballads – see below:

Bob and Don Stewart were joined by NCA Senior Legal Advisor, Greg Smith, in a hearty rendition of ‘Danny Boy’

THE SPECIAL INVESTIGATIONS UNIT

Eighteen months after Bob left the NCA our professional paths were to cross again, when I joined him as his Deputy at the Special Investigations Unit (SIU). The details of this event are dealt with in my book ‘Justice and War Crimes’ so there is no need to repeat them here. Nor do I intend to repeat the matters set out in Mark Aarons address at Bob’s memorial service following his premature death at the age of 60 (see below).

Shortly after I joined Bob at the SIU in September 1988, he said he wanted me to accompany him and Bruce Huggett, the SIU’s Chief Investigator, on a worldwide visit he had planned. The purpose of this mission was to establish or cement existing relationships with other institutions, organisations and archives involved in the investigation of Nazi war criminals. It was not to be an investigative mission in the sense we were going to gather evidence. He said he wanted me to accompany him so I could be introduced to the important players throughout the world.

Having only commenced duty with the SIU on 12 September, shortly thereafter on 20 September I departed Sydney with Greenwood and Huggett on a whirlwind worldwide trip to Europe and the Middle East (Italy; Israel; West and East Germany; France; and England) followed by the USA (New York; Washington DC and San Francisco). We arrived back in Sydney on 24 October 1988. For me the mission was very useful and a huge success, as it opened many doors for our future investigations and helped build trust with international organisations.

This was a dynamic introduction to the world of war crimes investigations and I met many of the world’s international leaders and players in the field. The contacts and connections made during this trip became invaluable when I later became the SIU’s Director when Bob left the Unit in April 1991 to resume his practice of law, this time at the Sydney Bar.

Following this first overseas mission with Bob, we travelled together on three other missions, all to the Soviet Union (via London). On the first of those we departed Sydney on 24 April 1990, bound for Moscow and Rovno, in relation to the SIU’s prosecution of Ivan Polyukhovich.

Moscow, 28 April 1990 (en route to Rovno)

Bob at a Moscow street market on 28 April 1990

May Day parade in Rovno 1 May 1990 – from left Bob Greenwood; Rovno interpreter Stas Kostetsky; Moscow Procurator General Natalia Kolesnikova; Sydney barrister Greg James QC; author; and SIU interpreter, Ludmila Stern.

The two men either side of Madam Kolesnikova were Rovno Procurators, Melnishin and Leonid.

May Day parade in Rovno, 1990.

Bob Greenwood addressing a group in Rovno in May 1990 – from left Greg James QC, SIU interpreter Ludmila Stern and Bob Greenwood, standing.

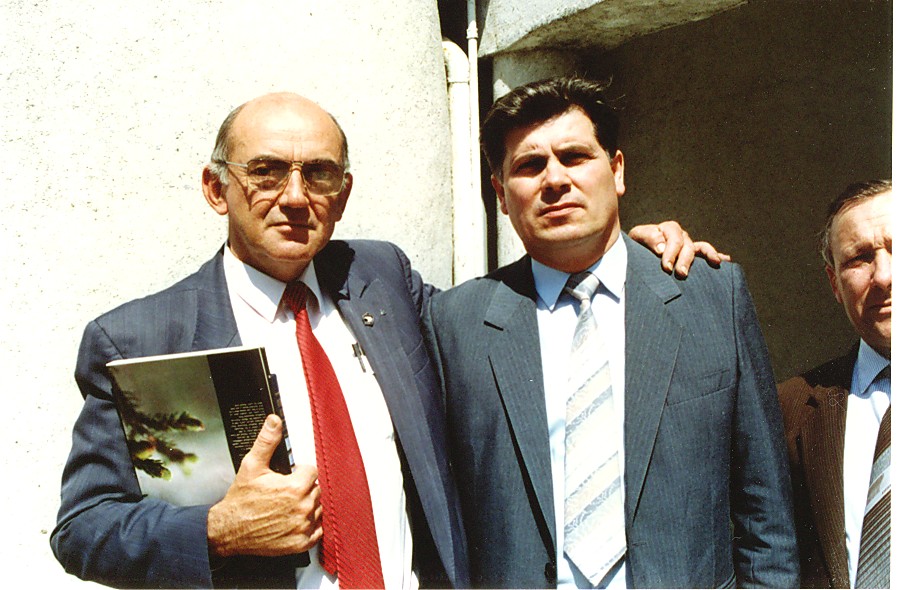

This photograph was taken during the team’s visit to Rovno in May 1990, to strengthen the SIU’s cooperation with the Rovno Procurators Office in the SIU case involving Ivan Polyukhovich. During the visit there was a dinner hosted by the Regional Prosecutor General, Vasily Polevoy (the man standing next to Bob – above). During the latter stages of the dinner, Bob and Polevoy engaged in a vodka for vodka toast. After 23 toasts, and at 2:30 am, Polevoy conceded defeat and embraced Bob, giving him a bear hug so powerful that he unintentionally broke several of Bob’s ribs. Remarkably, I took this photo the following day. Clearly Bob had won the contest – despite the pain from his broken ribs.

From left to right: Bob Greenwood, Moscow Procurator General Natalia Kolesnikova, Vasily Polevoy and Greg James QC (Sydney Barrister assigned to prosecute the Polyukhovich case).

Farewell gathering in Rovno in May 1990 – (Bob Greenwood fifth from the left; author fourth from right) with members of the Procurator’s office and SIU interpreter Ludmila Stern, fourth from left).

The second overseas mission with Bob was when we departed Sydney on 24 October 1990 on our way to Riga and Moscow, via London. This was an investigative mission with the objective of gathering evidence in respect of several SIU suspects, including Karlos Ozols.

SIU team members at Wembley Stadium 27 October 1990 – on the team’s way to Riga/Moscow. (We were attending a Rugby League Test, Aust -v- England (Australia lost 19-12)). From right to left: SIU Investigators Bill Beale, Michelle Kilburn, and Keith Conwell and SIU Director Bob Greenwood.

My last overseas trip with Bob was to Ukraine and the objective was to finalise arrangements for the Ukrainian witnesses to testify in Australia, and in relation to the two remaining mass grave exhumations to be undertaken by the SIU forensic team a few months later. We departed Sydney on 7 March 1991, travelling to Moscow then Vinnitsa (regarding the Heinrich Wagner prosecution) and Gnivan (for the Berezovsky prosecution).

SIU Team in Vinnitsa, on 16 March 1991 – from left: Tanya Ryvchin (SIU interpreter), Martin Dean (SIU historian), Ludmila Stern (SIU interpreter), Paul Malone (SIU investigator, in charge of the Berezovsky case), Bob Greenwood, with Local Procurators ‘Pavarotti’, Demar and Temchenko.

Sadly, following this mission with Bob, he left the SIU on 1 April 1991 at the age of 50. The following day I took over as the Director of the SIU, I was aged 44.

Bob and I remained in regular contact. When the SIU (or more accurately it’s successor in name, the War Crimes Prosecution Support Unit) finally closed its doors, a farewell function was held to mark the occasion in Sydney on 28 January 1994. At the event, Bob gave the opening address recounting the remarkable achievements of the SIU and its dedicated staff.

I will always treasure the relationship and friendship I shared with Bob Greenwood, one of life’s true champions.

What follows is Bob’s official Obituary after his death on 21 October 2001, followed by Mark Aarons’ address at Bob’s Memorial service, eight days later.

Obituary

Robert Francis Greenwood Q.C. 1941 – 2001

Bob Greenwood Q.C. is known to a wider world as the former head of the Australian Special Investigations Unit set up to investigate allegations of war crimes against persons in Australia.

He had, prior to taking up that challenging role, been a member of the National Crime Authority and Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions for the Commonwealth of Australia in the Australian Capital Territory.

Bob was a skilled criminal trial defence advocate who had achieved notable successes at trial and on appeal, including in the High Court. In his earlier career he had practiced particularly in the north of Queensland. He had taken up practise in New South Wales following his resignation from the Special Investigation Unit.

He died on Tuesday 23 October 2001, following a farewell function organised by his family and friends, which he was able to attend at Centennial Park on Sunday 21 October 2001, his 60th birthday.

He leaves his family, Janet, Anne, Bill, John, Sally, Michael and Harry with the fondest of memories of him.

At his memorial service at St. Andrew’s Cathedral on Monday 29 October 2001, his children spoke of their affection for a father for whom they had the highest regard.

Justice Mary Gaudron of the High Court described him as a man dedicated to the law, unswerving in his belief that all are answerable to the law and entitled to the law’s protection. He was a man, she said, who lived his beliefs. She described him as single-minded, fearless and sometimes slightly Fenian, generous, irreverent, irrepressible.

Mark Aarons, author, described the diligence and skill with which Bob had performed his function as head of the Special Investigation Unit obtaining the co-operation of the Soviet authorities in providing assistance including the provision of witnesses to the Australian prosecutions in consequence of the Unit’s investigations.

Those that knew him admired the man and respected the lawyer. His friends who were many will miss him very deeply.

BOB GREENWOOD – MEMORIAL SERVICE,

29 OCTOBER 2001 – MARK AARONS

In August 1987 a remarkable confrontation occurred in the dying days of the Cold War. Six months earlier, a young Australian lawyer had been given what many believed was the impossible task of investigating and, if possible, bringing to justice hundreds of Nazi mass killers who’d made Australia home.

Bob Greenwood QC had taken up the job of Director of the Special Investigations Unit on April the 1st 1987. He’d literally begun from scratch. After reading the few files available, the newly appointed war crimes investigator went to see the Attorney General.

Lionel Bowen was then also Deputy Prime Minister, and was to become one of Bob’s few supporters. Bob had thought carefully about the complexities that confronted him. He told the Attorney that his task would be impossible unless the communist authorities in Moscow agreed to allow their citizens to give evidence in Australian courts.

A wave of disbelief spread through the bureaucracy. The mandarins of the Department of Foreign Affairs declared Bob’s plan was crazy. He had ‘Buckley’s chance’ of convincing the communists to send their witnesses abroad.

Over the previous forty years, other Western nations had tried without success. Even the United States had been forced to send prosecution and defence counsel to tape evidence under the watchful eye of the KGB. What hope was there for a small time player from a tiny corner of the Western Alliance?

Characteristically, this didn’t daunt Bob Greenwood. He threw himself into a wearying round of meetings in which the communist officials were ‘very enthusiastic in their stated support for what we were doing.’ After several days Bob broached the subject of Soviet witnesses travelling to Australia.

The response was swift and predictable. Nyet, nyet and nyet again. Not under any circumstances. In his typically matter-of-fact way, Bob has recorded his confrontation with some of the toughest players in the Cold War: ‘I realised I just had to pull something out of the hat to try and clinch that understanding, otherwise you might as well pull up stumps and forget about any trials.’

Bob then gruffly played his cards, threatening to tell his government – and the rest of the world for that matter – that ‘due to the lack of co-operation of the Soviet officials the whole project would have to be aborted’ and that ‘the Soviet Union’s stated concern to see that Nazi war criminals received their just deserts was just a lot of hot air.’ Within a few days, agreement was reached: Soviet citizens would come to Australia.

Bob Greenwood had done what no one – even his own government – had believed possible. He had looked the Soviet Union in the eye and the communists had blinked.

Bob’s success was the start of a long line of ground breaking ‘firsts’ which placed him among the elite of his American, Canadian and British colleagues. Over the following years, he used his Australian larrikin charm to forge a unique brand of diplomacy.

On one occasion Bob matched a senior KGB officer vodka toast for vodka toast at a long dinner in the Ukraine. His host was vital in getting the war crimes investigators access to the evidence in several major cases, and after 23 toasts Colonel Poluvoy was utterly entranced by his guest. At half-past-two in the morning the Colonel embraced Bob, and gave him a bear hug so powerful that he broke several ribs.

Treatment at the local hospital turned out to involve electric shock therapy, which Bob wryly observed ‘was a fairly quaint way of treating broken ribs.’ None the less, his job was done and Colonel Poluvoy became a major ally in breaking through Soviet red tape. More importantly for Bob, he scrubbed up better than Poluvoy the next morning, broken ribs and all.

Other breakthroughs followed. Bob and his team became the first Westerners to conduct their own exhumations of Soviet mass graves. These established the scope and full horror of the mass killings carried out by their suspects. The archaeological digs revealed hundreds of bodies of innocent men, women and children – including the youngest babies and the oldest great-grand-mothers. They were carefully pieced back together, their shoes and other belongings gathered and catalogued and the bullet shells collected and analysed.

Before he threw himself into war crimes investigations with the commitment that characterised all his work, Bob Greenwood had known almost nothing about such mass killings. Indeed, he’d previously led a somewhat insular life, practising criminal law. His new job took him to almost every corner of the globe, and irrevocably changed his outlook and broadened his horizons.

Last December, I spent several hours with Bob, taping his memories of these investigations. In answer to a question about how these inquiries had affected him personally, Bob suddenly began to weep – quietly but passionately – as he described a visit to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Israel.

He described a darkened room with thousands of star-like lights representing the children who’d been murdered by the Nazis, and the soft voice intoning their names. He remembered the tears he’d shed as he realised what the Final Solution had really been all about. More than thirteen years later, Bob could not stop himself from crying all over again.

Indeed, even as he himself was dying a few days ago Bob’s concern for these long dead children was a recurring theme in his conversations with his closest family. It distressed him greatly that the world hadn’t learned from the Nazi murders, and that such killings were continuing even now.

This passion led Bob Greenwood to throw himself wholeheartedly into the war crimes investigations. To Bob, it was a simple matter of justice. Crimes had been committed. The people who carried them out were in Australia. If evidence was collected capable of establishing a prima facie case, then they should be brought before the court system.

It was a view not shared by some of his colleagues in the legal profession. Even more, it was not popular among politicians – on both sides. At first Bob was attacked by the conservative side, which vigorously opposed war crimes investigations. Some smeared his good name in parliament, and attacked his work in the media. Typically, Bob gave as good as he got, and became a powerful advocate for his work.

In the first few years Bob was strongly supported by Lionel Bowen. Indeed, it was Bowen who ordered the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation to open its files on suspected Nazis. This led to another series of confrontations between Bob and his own side of the Cold War.

The first few files confirmed what had been only circumstantially known before. Australia’s spies had recruited Nazi mass killers in the Cold War battle against communism. Bob was outraged and began to push the spy masters to release more. They resisted, and Bob had a series of toe-to-toe arguments with senior ASIO officials. In the end, he reluctantly withdrew from this battle, and concentrated on collecting evidence overseas.

By 1990, political support for Bob’s work was waning. After Lionel Bowen retired, and Bob Hawke was replaced as Prime Minister, support collapsed. The Keating government rushed to close the inquiries down, and Bob found that Canberra’s doors were shut firmly in his face. The bureaucrats in the Attorney General’s Department had always opposed the investigations, and now they used all their guile to undermine his efforts.

In April 1991, wearied by the endless obstacles, Bob returned to the Bar. He left behind him a team of dedicated professionals who had proudly called him ‘boss.’ Indeed, his successor, Graham Blewitt has said that Bob was ‘one of those people you would follow to hell and back, without asking questions.’

For all his clever diplomacy and passionate commitment, Bob’s effort was wrongly portrayed as a failure. Three prosecutions were launched, and a fourth shelved by the Keating government. No convictions were recorded, although the three cases that made it into the courts were three more than the critics had ever thought possible.

Bob Greenwood’s work as a war crimes investigator has left a lasting legacy. For a few years Australia held its head high on the international stage, where war crimes prosecutions are an everyday duty. The closure of the war crimes unit in 1992 left a bitter taste in Bob’s mouth, especially as he’d warned the government that Australia was once again providing sanctuary for war criminals.

In his last days as head of the unit, Bob proposed that its brief be extended to include modern war crimes. Ten years later, his warning has come true. Australia now shelters hundreds of mass killers from many conflicts – from the Khmer Rouge, through Pinochet’s police, to Afghani communist secret police and Serbs and Croats who committed crimes in the Balkans wars of the 1990s.

Their presence here distressed Bob. He hoped that an Australian government would finally take a stand, and enact what he termed ‘vermin laws’ to rid his country of this stain.

It was, however, a matter of pride to Bob that many of his team went on to carry Australia’s flag with pride on the international stage. It pleased him that Graham Blewitt is the Deputy Prosecutor of the Yugoslav war crimes Tribunal in The Hague, and that many other Australians have joined him there.

Their ongoing commitment to human rights and to justice for the victims is a reminder that Bob Greenwood’s work at the Special Investigations Unit was not wasted.

It is fitting that Bob’s work will be honoured forever by the Australian Jewish community. Today the community has announced a scholarship for indigenous law students at the University of Technology in Sydney to ‘be granted in perpetuity in memory of Bob Greenwood QC, and to honour his work, his life and his commitment to fighting racism.’

For Bob’s family – Janet, Anne, Bill, John, Sally, Michael and Harry – this is a permanent reminder of his decades of passionate commitment to Aboriginal justice, and his determination that all children should have a peaceful upbringing and a decent education.

(Mark Aarons)